One day before the lunar New Year’s Eve, I asked my manager to have a day off, explaining that according to Vietnamese traditions, the first day of the lunar year is dedicated to rest as a wish for leisure time in the coming year.Surprisingly, my manager, a young man from France, approved my request as long as I would bring some pieces of nem ran (fried spring roll) when I returned to work. He said he would in return bring in some wine so we could celebrate the Lunar New Year.

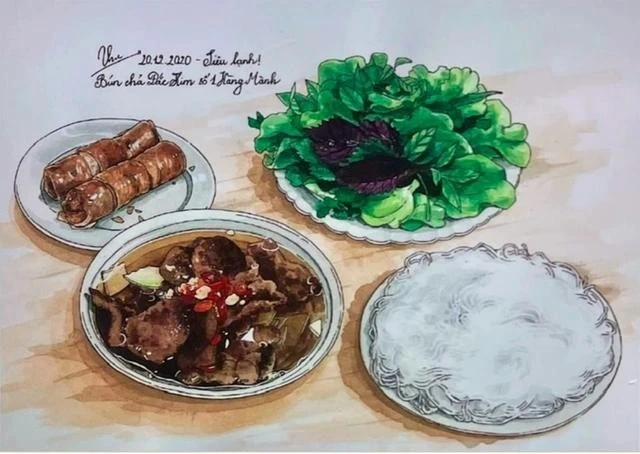

He then told me about his uncle, who had lived in Indochina and Hong Kong and had an interest in Vietnamese dishes, such as Pho (noodle), bun cha (rice noodle served with grilled pork), banh cuon (steamed rolled rice pancake), and especially, nem (spring roll). His uncle had taken him to Vietnamese restaurants, to share with his nephew his love for Vietnam’s nem.

The conversation with the French man took me back to the old days. I remember Tet during wartime when I was always so excited to breathe the delicious smell of nem.

Nem is an ensemble of natural ingredients and flavours, including rice paper, pork belly, onion, fungus, vermicelli, eggs, pepper, shrimp, sea crab, carrot, kohlrabi and bean sprout. The stuffing is minced, seasoned and kneaded together with all colours of the spring.

The mixture is then rolled in flat rice paper and fried in at a heat which is low enough to avoid the cover from being broken while high enough to make the paper crispy.

The dish is served with fresh salad type vegetables and a sauce which is a mixture of water, sugar, lemon and chili.

The sophistication of cooking nem once made it a great luxury; rich families used to consume it only during celebrations.

As it was made for royal members and upper class, the French named it ‘Pâté Impériale’ (royal pastry filled with meat).

Nem, which originated from the northern region of Vietnam, is different from Lao som moo (pork sausage), which tastes like Vietnam's nem chua (fermented pork roll) and China’s chunjua (egg roll), which has less ingredients with thicker paper.

At first sight, Vietnam’s nem looks like China’s chunjua, that is why it was once mistakenly called ‘egg roll’ in the English language. This misunderstanding led people to believe that nem originated from China.

Vietnam’s nem is more elegant in appearance as it uses thinner paper and has a greater diversity of flavours. Plus, the sauce accompanying this delicacy is made using fish sauce, a Vietnamese signature ingredient.

The French, who were present in Indochina and China for generations can spot the difference and offer great praise to Vietnam’s nem. Even France’s Larousse dictionary listed nem as a ‘spécialité Vietnamienne’ (specialty of Vietnam).

Visitors to a country not only want to enjoy the natural landscapes there but also strive to experience indigenous cuisine. It is cheese in France, sushi in Japan, spaghetti in Italy and in Vietnam, it is nem.

Today, nem can be found many big supermarkets in Europe, particularly in France and frozen nem have been exported to many other countries to meet the huge demand and appreciation for the dish.

Vietnamese people in the US, UK or English speaking countries who are doing business there should keep the Vietnamese name of nem or cha gio as the dish is called in southern region instead of ‘egg roll’, much like Italy’s spaghetti and pizza and Japan’s sushi are presented on a menu. By doing so, we can identify that nem or cha gio is a specialty of the Vietnamese people.

Cuisine is a part of culture, and the essence of cuisine is also the soul of a country’s culture. The preservation of a country’s culture not only includes the preservation of language, religion and music but also includes the protection of cuisine. Thus, protecting the country’ cuisine contributes to the protection of our cultural values.