A Palestinian heart with Vietnamese blood

Speaking Vietnamese imbued with the flavour of folk verses, skilfully weaving in idioms, proverbs and classical references after 15 years in Viet Nam, Saleem no longer considers himself a guest. He sees himself as a son of this land, carrying a Palestinian heart yet “Vietnamised in blood, having grown up on the rice grains and sips of water here”.

Once widely known through numerous gameshows and television programmes – as we jokingly put it, “Saleem ventured into showbiz” – he is now busy running a Palestinian restaurant in the heart of Ha Noi’s Old Quarter. Saleem first set foot in Viet Nam to pursue university studies on November 25, 2011. After graduating, he returned to Palestine to work at the Police Academy. Yet after just nine months, he decided to come back to Ha Noi.

“That was the most important decision of my life,” Saleem recalls. “At the time, the job in Palestine was a dream for many young people my age. But I had a different goal. I did not simply want a job; I had a bigger dream – to build a bridge between our two countries.”

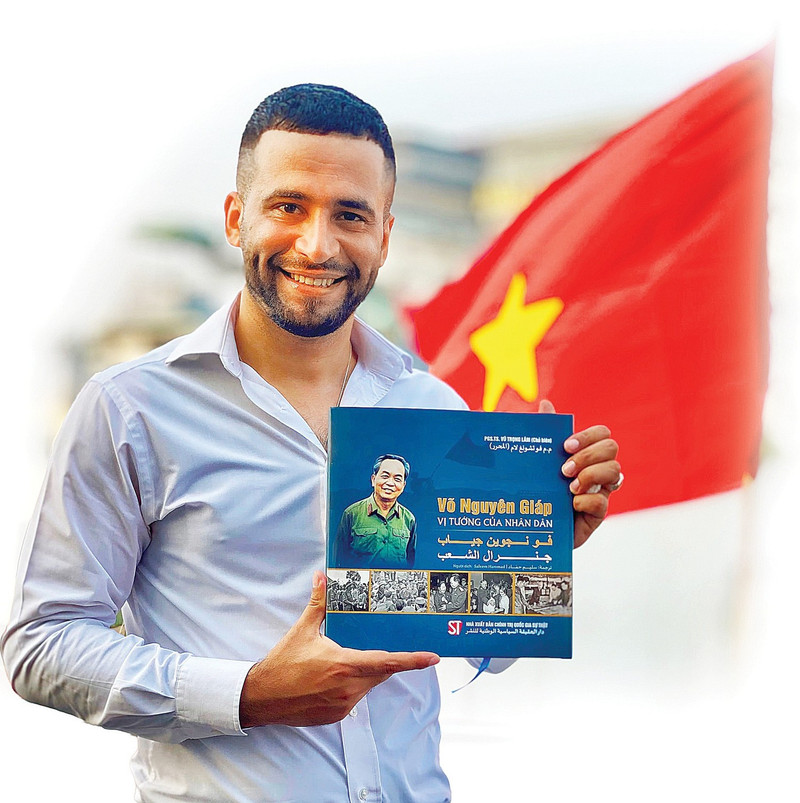

For more than a year, dedicating three to five hours each day, Saleem took part in three translation projects, rendering major Vietnamese works on history and political diplomacy into Arabic. These included “Vo Nguyen Giap – The General of the People”, edited by Associate Professor Dr Vu Trong Lam, Director and Editor-in-Chief of the Su That (Truth) National Political Publishing House; “Building and developing an advanced Vietnamese culture rich in national identity; and “Building and developing a comprehensive, modern Vietnamese foreign affairs and diplomacy with the distinctive ‘Viet Nam bamboo’ identity” by the late General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong.

Upon returning to Viet Nam, he formed a clearer ambition: to become a content creator and influential connector between Viet Nam and the Arab world. Moving away from the glamour once associated with showbiz, Saleem turned towards the beauty found in the value of labour.

The year 2025 marked another turning point. On his journey to establish his own restaurant, Saleem encountered communities engaged in Vietnamese agricultural produce and ancient tea. Every weekend, setting aside his busy urban schedule, he and his colleagues visit clean agricultural processing facilities and fruit and vegetable farms to film promotional content. At the same time, he explains Islamic culture to Vietnamese audiences and introduces a resilient, peaceful Viet Nam to the Arab world.

Throughout this journey, Saleem has sought an answer to a pressing question: how can it be that nearly two billion Muslims worldwide remain largely unaware of Viet Nam’s Halal-certified agricultural produce? He asks himself: “How can Vietnamese produce – how can Vietnamese identity – spread across the global map?”

From the perspective of someone representing a community of 22 Arabic-speaking countries, Saleem speaks candidly: “One quarter of the world’s population is Muslim. Yet when they come to Viet Nam, their greatest difficulty begins with their stomach.” He draws a comparison: Thailand welcomes millions of visitors from Muslim-majority countries thanks to its wide range of Halal-compliant restaurants, while Viet Nam remains relatively hesitant in this niche market. “When Muslim tourists arrive at the airport, the first thing they look for is suitable food. The scarcity of certified establishments has unintentionally created a barrier, leaving Viet Nam’s tourism industry at a disadvantage,” he analyses.

Bringing Vietnamese produce to a two-billion-person market

In promotional projects at production facilities or seminars where he is invited as a speaker, Saleem often emphasises: “Halal is not something complicated or mystical. It simply means cleanliness, humane processing, and compliance with certain rules.” To address the culinary gap, he is also nurturing plans to open a purely Vietnamese restaurant using Halal-certified ingredients for Muslim diners. There, guests would enjoy pho, bun, crab soup and water spinach – all prepared with authentic Vietnamese ingredients and seasonings, but processed according to Islamic rites.

“In the Arab and Muslim world, there is an unwritten rule: if you want to understand a land, begin with its dining table.” While he understands this better than most, Saleem also recognises a paradox: Muslim tourists who love Viet Nam often choose to stay longer in other destinations simply because suitable dining options are more readily available there.

“Vietnamese people say, ‘Fine words butter no parsnips.’ It is the same for us Muslims,” he says. “Viet Nam does not lack food and does not need to import unfamiliar dishes. What needs to be done is to ensure that Vietnamese cuisine obtains Halal certification.”

He explains that Halal standards do not require changing flavours or spices, but rather altering the way ingredients are handled. “The chicken and the beef remain Vietnamese produce, but they must be raised and slaughtered humanely, cleanly and reverently. When someone eats a delicious bowl of pho and feels their faith is respected, they will love the people and this country forever,” explains the owner of the Palestinian restaurant on Hang Buom Street in Ha Noi.

Saleem’s project to introduce and promote Vietnamese agricultural produce not only opens opportunities to attract tourists from Arab nations, but also seeks to “awaken” the need for standardised Halal certification from production to processing stages.

Saleem’s project to introduce and promote Vietnamese agricultural produce not only opens opportunities to attract tourists from Arab nations, but also seeks to “awaken” the need for standardised Halal certification from production to processing stages. As a distinct standard within the Muslim community, Halal also symbolises the highest level of food safety and hygiene – rigorous enough to satisfy even the most demanding markets.

At present, Saleem has guided numerous co-operatives and enterprises in developing Halal food products, striving to create a “lever” for Vietnamese agricultural produce not only to travel further but also to secure premium positions on international shelves. His efforts have begun to bear fruit. Saleem Agricultural Road channel has been approached by co-operatives and representatives from several provincial Departments of Tourism seeking collaboration to stimulate visitor flows from the Middle East and Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia.