One of the key pillars in this process is the reorganisation of territorial administrative units, which not only to streamline the state apparatus, but more profoundly to establish a governance model that is efficient, flexible, and aligned with new spatial development frameworks. The reform of administrative organisation is no longer a matter of choice; it has become an urgent necessity, driven by the country’s practical need to strengthen regional connectivity, optimise resources, and reduce the cost burden of institutional compliance.

Beginning July 1, 2025, a two-tier local government model (provincial–communal) has been officially functioned nationwide, marking a significant turning point in Viet Nam’s administrative reform. A new system of legal documents and strong directives from the party central committee, particularly from General Secretary To Lam, have clearly defined this as “a revolution in the organisation of the State apparatus” in the new era.

Reforming local governance thinking

National restructuring in the domain of administrative and territorial organisation is understood as a process of reorganising the spatial configuration of power, governance functions, and territorial jurisdiction of the state apparatus. The goal is enhancing institutional performance and promoting sustainable development. Previously, Viet Nam operated under a three-tier local government model (province–district–commune) with administrative functions distributed across levels. However, since July 1, 2025, the country has transitioned to a two-tier model (province–commune), eliminating the intermediate district level which had long been seen as a “transit” layer but increasingly revealed inefficiencies in operation and high maintenance costs. In today’s context, where public administration systems are moving toward streamlining and digitalisation, removing intermediary layers is not just an organisational adjustment but a manifestation of a revolution on governance mindset.

The phrase “Reorganising the Nation” is used as a strategic metaphor for reshaping national structure, closely tied to a vision of thorough administrative reform with long-term orientation and strategic foresight. In this view, reform goes far beyond merely “merging or splitting” administrative boundaries—it involves fundamental changes in the management of power, resource allocation, and the organisation of the civil service system within the new territorial framework.

The ongoing administrative and territorial reorganisation has not been operating spontaneously but has been systematically and carefully prepared through core policy documents of the Party and the State. First, Resolution No.60-NQ/TW adopted by the 11th Plenum of the 13th Central Committee on April 12, 2025, clearly defines the task of “continuing to reform the State apparatus, enhancing national governance effectiveness and efficiency, streamlining staffing, and modernising local governments”. This is a principle-based resolution, laying the ideological and strategic foundation for the entire reform effort.

Building on that, the Politburo’s Conclusion No.126-KL/TW, dated March 21, 2025, serves to concretise the strategy, formally adopting the unprecedented policy of eliminating the district level in Viet Nam’s administrative history. This conclusion emphasises the importance of reconstructing the administrative model in a streamlined, efficient, and region-focused direction, while ensuring continuity and avoiding major disruptions to civil life and political stability.

The Law on Organisation of Local Government No. 72/2025/QH15, passed by the National Assembly on June 16, 2025, serves as the direct legal basis for implementing the two-tier government model. This law not only outlines the new organisational structure but also introduces the conceptual frameworks for “special zones” and “inter-provincial units”—administrative constructs designed to meet the demands of multi-regional and multi-sectoral economic development in the new era. Codifying the two-tier model in law is more than a procedural step; it reflects a firm political and legal commitment to thoroughly reforming the state governance system.

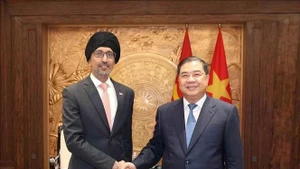

General Secretary To Lam, in his remarks at a meeting with the Ha Noi Municipal Party Standing Committee and during recent Politburo sessions, has underscored the comprehensive leadership role of the Party in the process of reorganising territorial administrative units. He emphasised that “innovating local governance thinking is a prerequisite for effectively implementing the two-tier government model”, asserting that without a shift in mindset, structural reform would be merely superficial. Following the General Secretary’s directives, the new apparatus must not only be streamlined in structure but must also operate on principles of proactivity, flexibility, public proximity, and high accountability. Eliminating the district level does not mean removing a layer of governance but rather entails a rational redistribution of functions between the provincial and communal levels, supported by information technology systems and clearly defined oversight mechanisms.

General Secretary To Lam emphasised that the commune level now plays a pivotal role as the administrative unit tasked with the most responsibilities and must be genuinely empowered in terms of finance, human resources, and local governance. To ensure the success of this transition, he directed a comprehensive review and reinforcement of grassroots personnel, along with enhanced policy support from the central government to promptly address challenges in implementing the new model.

Larger scale and greater socio-economic potential

Viet Nam’s current administrative-territorial restructuring is among the most extensive reforms in the country’s history. From the previous structure of 63 centrally governed provinces and cities, the nation has reorganised into 34 provincial-level units, including six centrally governed cities and 28 new provinces. This represents a nearly 46% reduction in provincial-level administrative units, resulting in larger territorial entities with stronger socioeconomic potential, greater competitiveness, and improved regional connectivity. At the same time, the district level, which was the intermediary tier in administrative management, has been eliminated, giving way to a streamlined two-tier local government model (province and commune).

The reorganised communes, wards, and townships now comprise approximately 3,321 administrative units, operating under a “multi-functional, comprehensive, and community-oriented” model. This approach aims to bring the government apparatus closer to citizens and businesses, eliminate bureaucratic intermediaries, and increase both accountability and responsiveness at the grassroots level. The nationwide rollout of the two-tier local government model (province and commune) is the result of thorough institutional preparation, including the passage of the Law on Organisation of Local Government No. 72/2025/QH15 by the National Assembly, personnel assessments, boundary adjustments, and the standardisation of administrative procedures.

The new model is characterised by three key features. The first is the enhancement of regional integration. The merger of provincial-level administrative units based on geographic, cultural, and socioeconomic clusters helps dismantle rigid boundaries and facilitates inter-locality cooperation to jointly leverage shared potential. The second is the robust decentralisation. Local governments, especially at the commune level, are granted significant autonomy in various areas, from issuing small-scale investment permits and managing land use to organising public services at the community level. The last one is the increased accountability. A more rigorous system of monitoring, evaluation, and oversight has been established to ensure that power is exercised alongside clear responsibility and transparency.

Moreover, the new administrative model reflects spatial development flexibility. Administrative boundaries are no longer strictly determined by natural geography; instead, they are designed based on functional zones, combining mountains, coastal areas, urban zones, industrial parks, and agricultural regions into interconnected and integrated structures. This reflects a shift toward administrative planning aligned with sustainable development and ecosystem-based regional governance. Though still in its early stages, the new model has already yielded some positive initial outcomes. The 46% reduction in provincial-level administrative units has significantly cut down on the layers of command and control, minimised overlapping functions, and reduced the cost of running the state apparatus. Indirect staffing, previously a large component of the intermediary management structure, has been efficiently trimmed, allowing for the reallocation of resources to frontline service positions.

Commune-level governments are now granted greater authority across budgeting, personnel, and self-governance mechanisms. Many communes and wards have adopted e-government platforms and are offering high-level public services, enabling citizens and businesses to access administrative services locally without needing to go through the now-dissolved district level.

Investment in regional connectivity infrastructure has been accelerated following the mergers. The government has prioritised transport and telecommunications projects linking areas within the same newly formed administrative units, creating a more efficient administrative, economic, and social network. This has not only reduced service disparities between central and remote areas but also fostered internal integration and more equitable development within each new province. Nevertheless, the implementation process faces several significant challenges. The transitional management of former district-level functions is not yet fully stabilised. Many administrative coordination and management roles remain ambiguously assigned, unclear whether they fall under provincial or communal responsibility, leading to overlaps or service gaps in certain sectors. A shortage of high-quality personnel at the commune level also poses a considerable barrier. As this new model demands greater responsibility and professional capacity at the grassroots, the lack of adequately trained staff could hinder its full realisation. Some localities still lack sufficient personnel in key fields such as planning, natural resources and environment, and public investment.

Additionally, the decentralisation among the central, provincial, and communal levels remains inconsistent, especially in areas such as finance, land management, and public investment oversight. Horizontal and vertical oversight mechanisms lack coherence, leaving many communes in a passive position, reluctant to make independent decisions. In addition, people and officials still have many doubts. Several mid-level officials have experienced demotion or job restructuring, leading to uncertainty and dissatisfaction. Meanwhile, residents in newly merged areas are still unfamiliar with new names, administrative boundaries, and service access procedures, resulting in confusion during the initial phase of implementation.

Redefining development spaces and institutional operating mechanisms

The shift from a three-tier to a two-tier government structure, combined with the merging of smaller administrative units, has created opportunities to redesign a governance framework more suited to the demands of modern socio-economic development. First and foremost, it enables the establishment of new development spaces. Larger-scale administrative units allow for the reorganisation of population distribution, the reallocation of economic and technical infrastructure, and the long-term, holistic planning of production and service zones. Rather than being fragmented by provincial or district-level borders, the new administrative framework facilitates the formation of interconnected development regions, maximising the use of shared resources, infrastructure, and labour within an integrated system. Secondly, the two-tier model significantly reduces the operational cost of the state apparatus by cutting down intermediary structures, streamlining personnel, and eliminating redundant bureaucratic layers. Resources saved through this institutional reform can be reinvested in local infrastructure, digital transformation, and welfare programmes. Simultaneously, deeper decentralisation to the commune level enhances autonomy and local capacity to flexibly address community issues and deliver public services. This fosters a model of local governance that is agile, cost-effective, and responsive.

Territorial administrative reorganisation marks a structural starting point for implementing major policy frameworks such as integrated planning, smart urban development, green and digital transitions, and the safeguarding of national defence and security amid globalisation and shifting regional geopolitics. A core objective of this reform is to promote regional integration and holistic development. The merging of provinces and cities according to economic-ecological clusters creates administrative units large enough to integrate resources, population, markets, and scientific-technological capacity, laying the groundwork for dynamic growth regions.

For instance, the new Red River Delta region, with Ha Noi as its nucleus, can combine industrial strength, high-tech agriculture, financial services, and logistics to become the economic powerhouse of northern Viet Nam. An expanded Central Highlands, with Lam Dong as its core, can evolve from a specialty agriculture hub into a centre for logistics, eco-tourism, and renewable energy. These “super-localities” pave the way for dismantling narrow provincial boundaries and implementing effective regional coordination mechanisms. This in turn supports the development of inter-provincial, cross-sector, and interdisciplinary value chains.

The inevitable outcome is the emergence of national development corridors connecting major growth poles such as Ha Noi, the North Central region, Da Nang, the Central Highlands, Ho Chi Minh City, and Can Tho. These corridors carry not only economic significance but also serve as a foundation for a more integrated political-administrative structure, reducing redundancy and optimising national resources. The evolving model of “comprehensive functional regions” is gradually replacing the outdated notion of “independent administrative units,” aligning with the trend of state modernisation in the 21st century.

In today’s new context, the reorganisation of territorial administrative units must be regarded as a central pillar in the strategy of national restructuring, where governance thinking, institutional design, and execution capacity must be fundamentally renewed. The success of this reform not only enhances local governance but also lays a solid foundation for Viet Nam to achieve faster, more sustainable, and more autonomous development in the 21st century.

Ensuring effective administrative reorganisation

To synchronously implement institutional, organisational, financial, and social solutions, the foremost priority is to complete a coherent legal framework aligned with the Law on Local Government Organisation No. 72/2025/QH15. Transitioning to a two-tier government structure requires fundamental revisions to related laws, including the Law on State Budget, the Law on Public Investment, the Planning Law, the Law on Cadres and Civil Servants, the Law on Government Organisation, and the Law on Promulgation of Legal Documents. Relevant agencies must promptly review, amend, and issue sub-law guidance to ensure uniform implementation.

Concurrently, it is essential to reassess the entire decentralisation mechanism between central, provincial, and communal levels to prevent overlaps and contradictions in functions, responsibilities, and authority. The new model demands that each level of government must “know its role and responsibilities”, thereby avoiding the shifting of blame or management gaps caused by unclear regulations.

To meet the rising demands on commune-level human resources, targeted retraining and professional development programmes must be launched for commune officials and civil servants, particularly in budgeting, planning, public investment, information technology, and public service delivery. This should be accompanied by updated recruitment policies that attract qualified personnel to the grassroots level through flexible and appropriate incentives.

To address the administrative vacuum left by the elimination of district-level governments, the establishment of “regional offices” or “regional coordination centres” is recommended. These are not intermediary administrative bodies but rather professional institutions that facilitate cross-sectoral and inter-local coordination in areas such as transportation, healthcare, disaster prevention, and rural-urban regional development. A flexible, soft-power mechanism with sufficient authority can effectively replace the traditional administrative command role of the former district level. The administrative restructuring also necessitates changes in budget allocation and financial management mechanisms. A new budget system tailored to the two-tier model must be developed, clearly defining the leadership role of the provincial level and granting fiscal autonomy to communes. Communes and wards should have the authority to plan their budgets and manage revenue-expenditure within delegated limits to promptly meet local needs.

Crucially, digital infrastructure and e-government at the commune level should be prioritised as indispensable tools for the new administrative model. Electronic one-stop portals, task management software, digitised citizen databases, and feedback-reporting systems must be uniformly implemented to allow residents and businesses convenient access to public services without having to travel far or navigate multiple layers of bureaucracy.

In addition, policy dissemination and building social consensus must receive special attention. Broad-based information campaigns are needed to clearly explain the long-term benefits of reorganising administrative units for citizens, businesses, and society at large. Renaming localities, redefining administrative boundaries, and reorganising work units must be transparently communicated to prevent confusion, misunderstanding, or passive resistance.

The government must also establish two-way communication channels to gather opinions, feedback, and assessments from the grassroots level. These responses are crucial for adjusting policies, refining the model, and building adaptive governance mechanisms for the new era. Throughout this restructuring process, the central role of leadership, coordination, and oversight by the central government, particularly the Communist Party of Viet Nam, has been pivotal. Reforming the state apparatus cannot be a mere administrative decision; it requires comprehensive, consistent, and determined leadership from the central level to ensure smooth implementation and timely resolution of emerging bottlenecks.

Following the passage of Law No.72/2025/QH15, the Party Central Committee, the Politburo, and the Party Central Committee’s Organisation Commission have conducted multiple rounds of inspections and supervision across localities, especially in areas with ethnic diversity, border characteristics, or transitional regions. Task forces have been deployed to monitor progress and resolve challenges, from personnel arrangements to infrastructure restructuring and administrative procedure reforms.

General Secretary To Lam has played a strategic role in shaping and guiding this reform. In his directives during working sessions with Ha Noi’s leadership, he stressed the need to renew local governance thinking, prioritising execution capacity and effectiveness over formal structures; he called for bold, decisive cuts to unnecessary intermediary layers to strengthen administrative performance in service of the people. He also underscored that personnel reorganisation and staff streamlining must go hand-in-hand with capacity-building efforts, ensuring that political stability and organisational cohesion at the grassroots level are maintained. This proactive, flexible, yet synchronised leadership from the central level has laid a solid foundation for realising Viet Nam’s national restructuring goals through territorial administrative reform, anchoring political vision, governance capacity, and social consensus into one unified transformation.