Leader Nguyen Ai Quoc returned to the homeland on January 28, 1941, to directly lead the revolution. In May 1941, he presided over the eighth Plenum of the Party Central Committee, where crucial decisions were made on the strategy and tactics of Viet Nam’s revolution in the movement for national liberation, towards seizing power. Amidst the mountains and forests of Pac Bo, on May 19, 1941, at Nguyen Ai Quoc’s initiative, the Eighth Plenum of the Party Central Committee decided to establish the Viet Nam Independence League (abbreviated as the Viet Minh Front), with the declared objective of expelling the French and Japanese to gain independence and freedom for the nation.

The Viet Minh Front announced to the people that the aim of the Viet Nam Independence League is to bring freedom and happiness to the compatriots, to liberate the oppressed classes of people throughout this land of Indochina.(1)

To achieve this, the Viet Minh advocated the union of all strata of the people, regardless of religion, political Party, political tendency, or class, uniting in struggle to drive out the French and Japanese and gain independence for the country.(2)

The spirit of the Resolution of the eighth plenum and Ho Chi Minh’s ideology of national liberation revolution were translated into the Viet Minh’s Programme, with progressive policies in politics, economy, culture and society. These policies addressed the aspirations of all social strata, regardless of status or political tendency, and united them in the shared desire for an independent, democratic and prosperous Viet Nam.

The Party Central Committee’s Standing Board met in Vong La (Ha Noi) in February 1943, adopting the guideline of forming alliances with all patriotic Parties and groups inside and outside the Viet Minh Front, intensifying mobilisation among workers, peasants, soldiers, youth, women, patriotic capitalists and landlords, ethnic minorities, overseas Chinese, and establishing the National Salvation Cultural Association in cities to unite intellectuals and cultural figures.

The principle of consolidating and expanding the Front was that it must always consolidate and develop the organisations of workers and peasants because they are the backbone of the national united front against the Japanese and French. At the same time, it must vigorously expand the national salvation organisations of youth, women, capitalists, landlords, small traders, etc.(3)

“National Salvation” became the common slogan of the entire nation. It was also the name of the Viet Minh’s affiliated organisations: Workers’ National Salvation, Peasants’ National Salvation, Youth National Salvation, Women’s National Salvation, Cultural National Salvation, etc. Under the Party’s leadership, the Viet Minh Front united all forces, organisations, and individuals from all walks of life to achieve the common goal of “working together for liberation and survival.”

In a losing position, on March 9, 1945, Japan staged a coup against France to monopolise Indochina. While the gunfire of “Japanese and French fighting each other” was still echoing, the expanded meeting of the Party Central Committee’s Standing Board assessed that the opportunity for uprising was imminent – “Good opportunities are helping to ripen the conditions for uprising.”

The Conference promptly issued the Directive “Japanese and French fighting each other and our action” on March 12, 1945. Based on assessments and predictions of the situation’s development, the Party Central Committee’s Standing Board resolved to “launch a powerful anti-Japanese national salvation movement as a premise for the General Uprising.” The struggle slogan was: Drive out the Japanese fascists and establish a revolutionary government of the people.

On June 6, 1945, the Viet Bac Liberation Zone was established, covering six provinces – Cao Bang, Bac Kan, Lang Son, Ha Giang, Tuyen Quang, Thai Nguyen – as well as parts of Bac Giang, Vinh Yen, Phu Tho, Yen Bai, following the decision of the Viet Minh General Committee’s Cadre Conference.

In the Liberation Zone, the Viet Minh Front gradually assumed the functions of a people’s government. The Revolutionary Committee of the Liberation Zone and committees elected by the people implemented “Ten Major Policies of the Viet Minh.” In Cao Bang’s “fully liberated” communes, districts, and prefectures, guerrilla units operated vigorously. The Viet Nam Propaganda Liberation Army and the National Salvation Army attacked Japanese troops to expand the liberated areas, achieving victories in many places.

In rural lowlands, peasants launched struggles against uprooting rice and destroying crops for castor oil cultivation. In urban areas, especially in Ha Noi, revolutionary atmosphere surged amid urgent developments after Japan’s coup against France. Workers staged strikes for higher wages and against beatings, while movements among youth, students, and intellectuals grew stronger. The Viet Minh’s National Salvation organisations rallied broad masses of the people.

In Sai Gon, the Volunteer Youth organisations, and in Hue, the Frontline Youth, voluntarily joined the Viet Minh ranks before the uprising, operating under the Party’s leadership. Civil servants, soldiers and police of the puppet government became disoriented and shaken, with some siding with the revolution. The activities of propaganda brigades grew increasingly bold, widely resonating among the masses, fuelling the revolutionary momentum in the fervent days of preparation for the uprising. Puppet governments established in urban centres after Japan’s coup became isolated in the “heated” revolutionary atmosphere.

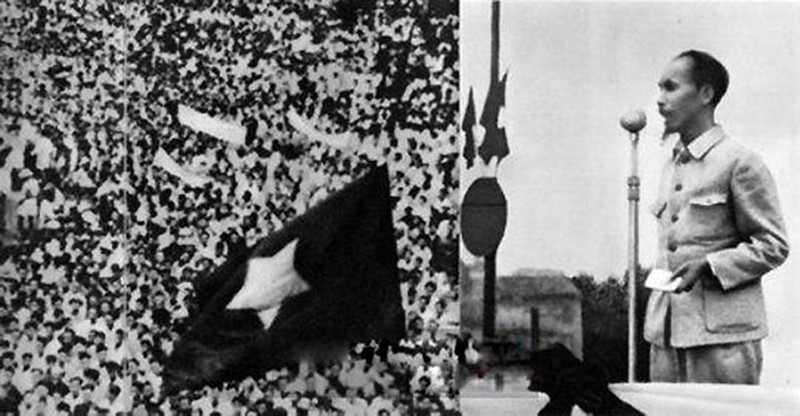

The Party grasped the opportunity with sensitivity, promptly mobilising the entire people to rise in uprising. The August General Uprising quickly achieved complete success nationwide. The united strength of the people created the miracle of regaining independence for the nation.

Writing about the victory of the August 1945 General Uprising, French historian Philippe Devillers remarked that it was also the logical result of the Viet Minh’s work in all areas of the country’s life.(4)

Through the Viet Minh Front, the Party expanded its role and influence across society, fulfilling the mission of leading the national liberation revolution. The Viet Minh Front was closely associated with the great victory of the August Revolution of the Vietnamese people. That victory bore the imprint of Ho Chi Minh’s ideology of great national unity. The historic milestones of the Vietnamese people in the 20th century all reflect the fruits of the strength of national solidarity. Party General Secretary To Lam affirmed: “The future, potential, position, and international prestige we enjoy today are largely the result of the strength nurtured by the great national unity bloc.”

The new context with new challenges demands that the strength of national unity be brought to a new height. The great lesson from the success of the past remains relevant. Party General Secretary To Lam stated the guiding principle clearly: “We are determined to preserve and promote the strength of national solidarity, regarding it as the ‘lifeline,’ the ‘red thread’ running through, ensuring that all guidelines and policies of the Party and the State are thoroughly, consistently, and effectively implemented, best meeting the legitimate aspirations of the people.” The unifying goal of national unity in the past was independence and freedom. The unifying goal of national unity today is prosperity and happiness. The key to arousing patriotism, self-reliance, confidence, resilience, and national pride for sustainable development in the context of global integration is to unleash the tremendous strength of great national unity.

References

[1] Communist Party of Viet Nam: Complete Works of the Party Documents, National Political Publishing House, Ha Noi, 2000, Vol. 7, p.149.

[2] Communist Party of Viet Nam: ibid., Vol. 7, p.152.

[3] Communist Party of Viet Nam: ibid., Vol. 7, p.294.

[4] Ph. Devillers: History of Viet Nam from 1940 to 1952 – Seuil Publishing House, Paris, 1952, p.132 – cited from The August 1945 General Uprising – Hoang Dieu National Salvation Youth Union – Viet Nam Association of Historical Sciences, Labour Publishing House, Ha Noi, 1999, p.473.