Refinement in the smallest details

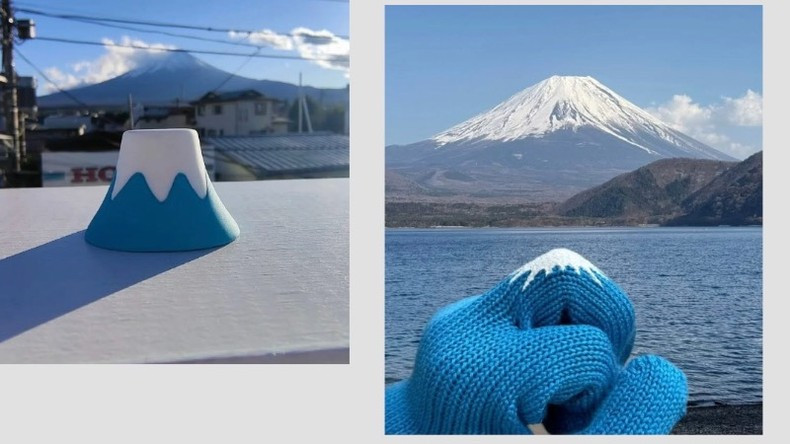

The Japanese have long demonstrated finesse and consistency in transforming cultural values into products. Mount Fuji — a sacred symbol — is not only immortalised in poetry, paintings, photography, and cinema, but also vividly reimagined in hundreds of souvenirs: candles, gloves, pens, keychains, sweets, notebooks, and phone cases.

|

| Mount Fuji depicted in Japanese souvenir items. |

Notably, the designs are uniform in image, color and aesthetic standards, helping Japanese souvenir products to be highly recognizable and easily spread.

|

| Consistent branding in imagery and colours strengthens Japan’s cultural identity. |

China has taken a similar approach. Even a simple decorative ball — commonly used in grand openings and ceremonies — has been developed into a complete souvenir line. From opera masks and peony patterns to traditional mascots, each element is standardised in design and effectively employed in diplomacy and international events. Their thinking is consistent: every souvenir tells a story of history, culture, and people. This, essentially, is the origin of national branding.

|

| The decorative ball acts as a cultural envoy for China around the world. |

Viet Nam possesses a wealth of intangible cultural heritage and one of the most diverse handicraft traditions in the region. Each craft village and region offers rich resources for developing culturally distinctive souvenirs. However, the current situation shows fragmentation, lack of connection and depth.

At many tourist sites, souvenirs are often generic: keychains printed with famous landmarks, mass-produced embroidered pictures, or repetitive miniature conical hats — none of which distinctly convey regional identities or leave a lasting impression of Vietnamese cultural branding.

One illustrative case is that of teacher Vi Thi Ai in Tua Chua District, Dien Bien Province. She brought over 20 embroidered pao balls and hair ties to Ha Noi from her local women’s association. Although these are intricately handmade, they sell for just a few dozen thousand dong. She hoped to modernise the pao — a traditional H’Mong item — into a diverse souvenir line, but lacked the necessary guidance.

Meanwhile, countries like Bhutan have elevated similar items such as festival masks and hand-embroidered scarves into national gifts that regularly appear at international trade fairs as spiritual symbols of their culture.

|

| Teacher Vi Thi Ai aspires to diversify souvenir products based on the H’Mong pao ball. |

A national strategy for souvenirs

Strategically speaking, souvenirs are a powerful and visual medium of cultural communication. In the Republic of Korea, the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA), under the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, plays a key role in planning, producing, and distributing various cultural content — including K-pop, dramas, games, comics, animation, influencers, and fashion — to promote the Korean Wave (Hallyu) and Korean cultural identity globally.

Each year, KOCCA selects cultural products to invest in, standardise, and incorporate into the national promotional ecosystem. Items such as Hanbok dolls, traditional masks, and ceramic tea sets are associated with core cultural symbols and are synchronised across touchpoints: from museum souvenirs to diplomatic gifts at international events.

These are not merely products — each is accompanied by storytelling and media promotion, amplifying their reach. In Viet Nam, KOCCA has co-organised numerous cultural events in Sa Pa, Hue, and Ha Noi, showcasing animated characters and traditional motifs with standardised imagery — something Vietnamese souvenirs still lack. Every small gift conveys a narrative, and each narrative reinforces brand identity.

It is time Viet Nam needs to develop a national strategy for souvenirs. Currently, efforts to build souvenir products remain piecemeal: occasional city-level design contests, some OCOP (One Commune One Product) stalls, or small-scale workshops in Hoi An, Sa Pa, or Hue. Elsewhere, product development is often improvisational, resulting in inconsistency and lack of lasting impact. These initiatives are active but lack integration and state-backed mechanisms to guide and elevate them into national cultural brands.

|

| The H’Mong pao ball contains layers of cultural value. |

To transform souvenirs into a national brand, there must be cross-sector collaboration — between the culture, tourism, industry and trade, foreign affairs, and communications sectors — to build a set of representative cultural symbols for each region and field. Heritage sites, cuisine, costumes, and beliefs can all serve as design foundations for artists, artisans, and businesses to develop meaningful souvenirs.

A set of core cultural symbols could be formed around key heritage sites (such as the Temple of Literature-Quoc Tu Giam, One Pillar Pagoda, Turtle Tower in Hoan Kiem Lake, or Central Highlands communal houses), traditional attire (such as the Ao dai or pieu scarf), and spiritual items (like the Dong Son drum, con shuttlecock, hat boi masks, or water puppets).

|

| A comprehensive strategy is needed to develop the souvenir sector from Viet Nam’s cultural resources. |

A crucial step is standardising the design process, materials, craftsmanship, and cultural narratives. Each product should have clear labelling that includes its name, origin, significance, and regional context.

In practice, many Japanese and Korean gifts are made from simple materials, yet they convey meaningful stories about their source and crafting process. This elevates their perceived value and encourages recipients to treasure them as cultural heritage artifacts.

Moreover, souvenirs must be present at key international cultural “touchpoints” — such as airports, museums, Vietnamese cultural centres abroad, global travel fairs, and diplomatic hubs. A professional distribution and communication network will enable these products to transcend local boundaries and represent national identity.

In the digital age, while technology enables rapid dissemination, it is cultural authenticity that creates distinction. Whether it’s a H’Mong pao ball, a Thai brocade bag, or a red-flag charm hanging on a student’s backpack abroad — all can become foundations for cultural branding when thoughtfully crafted. Every small gift is more than a product — it is a cultural message from Viet Nam to the world.