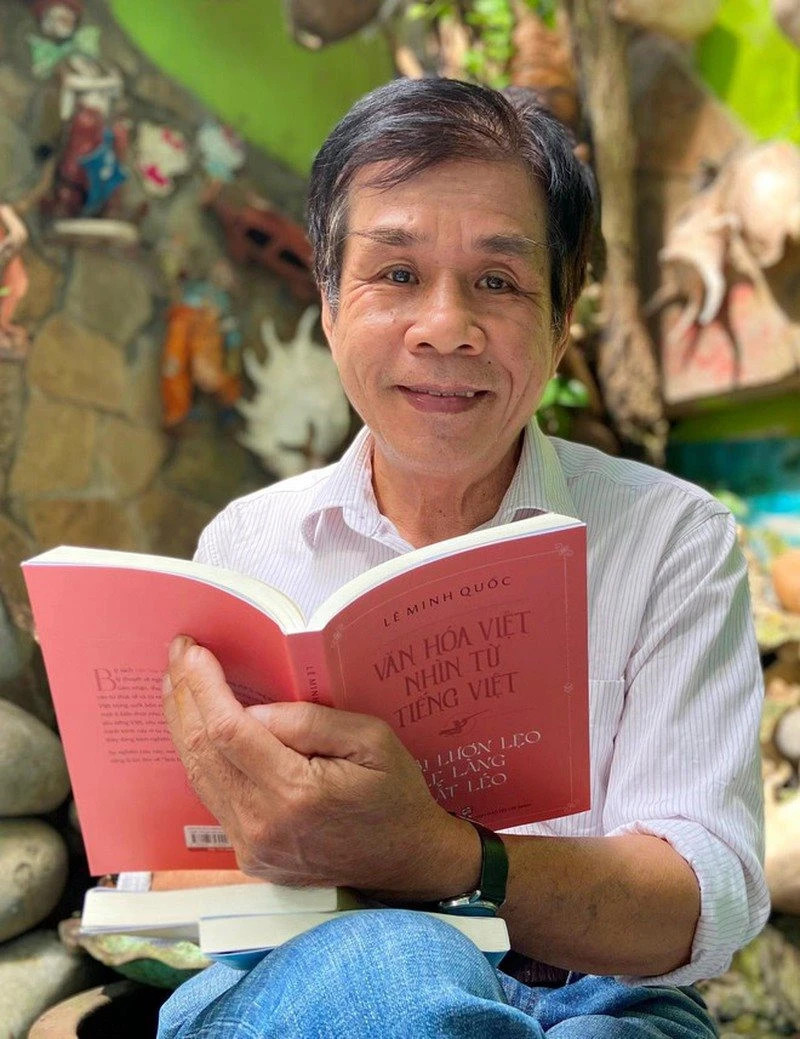

Q: In recent years, you have shown a deep interest in the Vietnamese language, with several books published on the topic, the latest being ‘Vietnamese – Complicated and Elegant’. What inspired you to take on this work?

A: It’s not just writers — those who live with words as their life’s calling — but most people have a need to explore themselves. After spending time with poetry and various literary genres, one day, I came to a rather ordinary realisation that I have read, learned, and remembered many poems, prose, folk verses, and proverbs, but have I truly understood them? And is my understanding necessarily the right one?

When I encounter a difficult word, I always recall the seminar “Cao Xuan Hao with Vietnamese Linguistics”, organised by the Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations (VUSTA) and the Ho Chi Minh City Linguistic Society on December 23, 2017. At this seminar, scholar An Chi raised a point that made him “question the existence of reduplication” and he demonstrated that “the elements before or after the 'reduplicated' combination are original Sino-Vietnamese morphemes with clear and specific meanings.” This was also a view affirmed earlier by the great linguist Cao Xuan Hao. This gave me the confidence to tackle words I previously found difficult to explain, and now, I am more determined to continue exploring their meanings.

Q: In the eyes of a devoted researcher like you, what risks is Vietnamese facing in current integration period?

A: This is undoubtedly a complex issue that would require a dedicated discussion or seminar to explore thoroughly. Let me share a small story. On a university lecturer's personal Facebook page, I was surprised to see him intentionally writing with spelling errors. When I pointed this out, he defended himself by saying that being on social media means accepting and using “internet language” to keep up with youth trends.

I did not argue, but I wanted to say that in the language of the young people in the current 4.0 era, youth is “tre trau” (a derogatory term for immature youth). What does this story illustrate? Clearly, we are witnessing the emergence of a “distorted Vietnamese language”, a “deformed Vietnamese language”, or a “slurred Vietnamese language”. Is this situation due to a lack of understanding of the Vietnamese language? No, they understand it; however, they intentionally write incorrectly for various reasons. This can be easily verified on social media with many examples.

Considering the historical struggles our ancestors faced, including the sacrifices made to resist foreign assimilation, it seems unreasonable that we would now carelessly toss in sand and gravel into the beautiful rice they carefully preserved for future generations, as a form of mockery or amusement.

Q: Many people are concerned that Vietnamese, in this technology-driven era, is becoming hybridised and losing its rich and nuanced beauty. However, others argue that we should embrace new trends, as they are inevitable in the process of societal development. How do you view the limits of such opinions?

A: To discuss this issue, let’s revisit the thoughts shared by satirical poet Tu Mo during a conversation with journalist Le Thanh in 1943: “At that time, the Finance Department was still by Hoan Kiem Lake. Within our department, we devised many beneficial games for improving our national language skills. For example, we agreed that anyone who spoke a sentence in Southern Vietnamese that included a French word, as was common among civil servants then and now, would be fined.” This story remains relevant today.

I believe that for specific objects or events, if the Vietnamese language has sufficient vocabulary to express them clearly and fully, then why should we resort to borrowing words from other languages? This strange usage was criticised by our ancestors long ago with many terms. Should we continue down this path?

With the current advancements in various fields, especially in science, technology, and informatics, if we do not have enough corresponding words in Vietnamese, borrowed terms seems appropriate. Once we accept this borrowing, if it persists over time, people will likely come to view it as part of the Vietnamese vocabulary, not distinguishing between “biological children” and “adopted children”. This reflects the tolerant and accommodating nature of the Vietnamese people. This practice enriches the Vietnamese vocabulary, as we have observed, particularly with borrowed terms since the early 20th century.

If not, borrowed words will eventually fade away, especially when Vietnamese alternatives exist. This is entirely normal, and it is difficult to pinpoint which borrowed terms will remain; we must wait for time to tell. Therefore, I think it’s okay for young people to use these borrowed terms, so long as they do not “overdo it”.

Q: Compared to previous generations, the current younger generation uses Vietnamese more flexibly, but they often lack a deep understanding of the language. Do you agree with this?

A: You are right. There are indeed new and playful phrases emerging in young people's speech and writing. It is quite interesting. I think it would be simplistic to say that the younger generation does not understand Vietnamese deeply. For me, the real issue arises when someone does not appreciate Vietnamese as it is and deliberately writes or speaks in a way that deviates from established norms. No matter the justification, nobody can accept these distorted and bizarre usages of Vietnamese.

Thank you very much!