The first population law to be introduced

Following the 8th session of the 15th National Assembly, many voters have proposed that given the significant socio-economic and demographic changes, new legal frameworks are required to comprehensively address population size, structure, distribution, and quality—ensuring rapid and sustainable national development. Accordingly, they have called for a revision and elevation of the 2003 Ordinance on Population and its 2008 amendments to a full Population Law.

At present, the Ministry of Health has completed the proposal dossier for the drafting of a Population Law and submitted it to the Government. The draft law focuses on three key policy areas: maintaining replacement-level fertility, reducing gender imbalance at birth, and improving population quality.

In recent times, several policies have been amended to encourage higher birth rates. Notably, the Politburo has ruled that Party members having a third child will not face disciplinary action. The draft amendment to Article 10 of the Population Ordinance, proposed by the Ministry of Health, allows each couple or individual to decide freely on the timing, number, and spacing of their children.

The draft law also proposes that maternity leave for a second child be extended to seven months. Women with two children working in industrial or export processing zones, or in provinces and cities with low birth rates, will be eligible for support to rent or purchase social housing—an initiative that is drawing considerable interest from workers.

Nguyen Thi Lan, a 28-year-old garment worker at Hung Yen Garment Company, shared: “In my workshop, many mothers have had to take a full year off after giving birth, including six months of unpaid leave to better care for their babies. That’s why we female workers are very pleased with the Health Ministry’s proposal to support mothers having a second child. Most of us are far from our families, so without support from relatives, we have no choice but to take extra leave after giving birth.”

Nguyen Xuan Duong, Vice Chairman of the Viet Nam Textile and Garment Association, stated: “Encouraging childbirth is vital in our female-dominated industry, even if these policies come somewhat late. Labour shortages are not far off. Female workers tend to extend their maternity leave, leading to manpower shortfalls—particularly during peak production periods. However, when considering having another child, workers and their families must weigh many factors, so it is essential that the State’s pro-birth policies also address housing, children’s education, and healthcare.”

In 2024, Viet Nam’s fertility rate was 1.91 children per woman—marking the third consecutive year it has remained below the replacement rate of 2.1. This level is insufficient to sustain population replacement. Viet Nam now has the lowest fertility rate in Southeast Asia.

If this declining trend continues, Viet Nam is projected to exit the “demographic dividend” period by 2039, and enter a phase of negative population growth by 2069.

The proposal to provide social housing for women with two children working in industrial and export processing zones in low-fertility areas has gained considerable attention. However, Dr Mai Xuan Phuong, former Deputy Director of Communications and Education at the Ministry of Health, noted that female production workers must be prioritised, and that three key factors must be considered: “First, policies must be attractive. Second, salary and maternity budgets must be balanced. Third, maternity and fertility incentives must be linked in a coherent policy framework.”

|

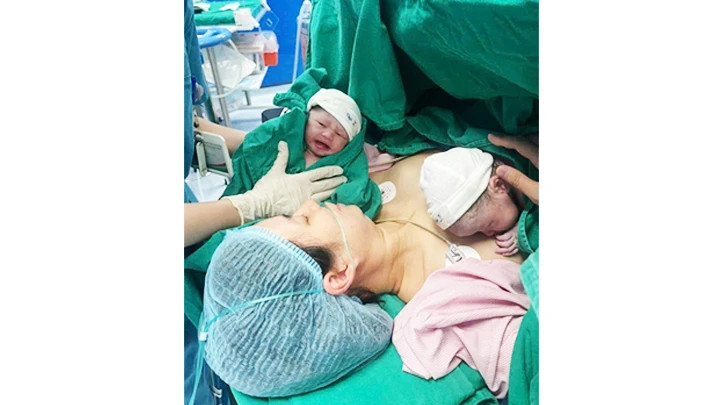

| Babies born through assisted reproduction at the Military Clinical Embryology Institute (Military Medical Academy). Photo: MINH TAM |

Barriers to infertility treatment

Increasing birth rates is also challenged by rising infertility and subfertility. Experts point to various causes. In men, these include abnormalities in sperm quality and count, hormonal deficiencies due to gonadal dysfunction, premature or retrograde ejaculation. In women, common causes include blocked fallopian tubes, pelvic infections, poor nutrition, advanced maternal age, ovulatory disorders, endometriosis, and ovarian tumours.

Lifestyle choices, environmental factors, and genetics also contribute to rising infertility rates. Unhealthy habits like frequent stimulant use, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, and poor diet all impact reproductive health.

Stressful working environments, exposure to radiation and electromagnetic waves can negatively affect sperm production, sperm maturation, and ovarian function. Unsafe or premature sexual activity can also harm reproductive organs, increasing the risk of infertility.

Major hospitals such as the National Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tu Du Hospital, Ha Noi Obstetrics and Gynaecology Hospital, the Military Institute of Clinical Embryology and Stem Cell Research, and Tam Anh General Hospital receive dozens, even hundreds of couples seeking infertility treatment daily. Their “longing for a child” often drives them to spend their life savings on treatment.

For instance, Mr H and Mrs K spent 21 years trying to conceive. Diagnosed with ovarian failure and azoospermia respectively, they travelled repeatedly across the country to renowned infertility clinics, spending hundreds of millions of Vietnamese dong each time. At last, thanks to advanced “sperm retrieval from testicular tissue” techniques at the Military Institute of Clinical Embryology, they welcomed a healthy baby, bringing joy to the entire family.

However, not all couples are so fortunate. Many exhaust their financial resources after repeated failed fertility treatments. Others, though eager to conceive, cannot afford the procedures.

Despite rising infertility rates, the number of treated cases remains low, mainly due to the high costs—ranging from tens to hundreds of millions of dong per cycle. Prof, Dr. Nguyen Viet Tien, President of the Viet Nam Association of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, stated: “Viet Nam’s infertility treatment technology has advanced rapidly. More than 50 centres nationwide now offer in-vitro fertilisation (IVF), with success rates reaching 60% for clinical pregnancy per cycle. However, these services remain costly relative to average incomes. The national health insurance fund does not cover these procedures, leaving many families unable to fulfil their dream of parenthood.”

Prof Tien proposed that health insurance should cover infertility treatment: “This cannot happen overnight due to funding limitations. Implementation should be gradual. For example, insurance could cover surgeries related to infertility, such as fibroid or ovarian tumour removal, before moving on to IVF and more advanced procedures once the fund is more robust.”

|

| The joy of a young couple upon receiving their prenatal screening results. (Photo: HAI NAM) |

Enhancing population quality

In addition to encouraging higher birth rates, experts stress the need to improve population quality through assisted reproductive technologies—key to achieving Viet Nam’s population strategy targets for 2030.

Today’s medical advances allow early detection of many genetic conditions. Among the most common is thalassemia (inherited blood disorder), with nearly 10% of the population carrying the gene. Viet Nam currently has over 12 million carriers and more than 20,000 severely affected individuals requiring lifelong treatment. Treating a severe case from birth to age 30 costs around 3 billion VND (115,700 USD). A patient with severe disease needs about 470 blood transfusions by age 21. Nationally, Viet Nam requires over 2 trillion VND (77.16 million USD) annually and 500,000 safe blood units to meet treatment needs.

To limit hereditary disorders, the draft Population Law proposes early detection through premarital counselling, prenatal and neonatal screening, enhancing workforce quality for national development.

The Military Institute of Clinical Embryology has pioneered genetic screening and fertility support nationwide. Since 2016, it has undertaken a state-level research project on diagnosing genetic diseases before embryo transfer during IVF. Since then, the institute has implemented preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic diseases (PGTm), initially screening a few disorders like thalassemia, haemophilia, and spinal muscular atrophy. Today, it can screen for around 400 genetic conditions.

The institute leads in developing reproductive genetics techniques that help carrier couples avoid passing on genetic diseases. “Genetic screening allows parents to give birth to healthy, disease-free children. This not only raises the total fertility rate but also improves population quality,” affirmed Colonel Associate Professor Dr Trinh The Son, Director of the Military Institute of Clinical Embryology.

“For families with a history of genetic disorders or abnormal blood test results suggestive of thalassemia, early testing is essential. Couples should undergo premarital genetic screening. We must enhance public awareness—Viet Nam can now screen for 400 inherited conditions, enabling families to give birth to healthy children. Randomly bringing children with genetic diseases into the world places a heavy burden on both families and society,” Dr Son warned.

From a social perspective, experts emphasise that improving population quality also means ensuring that every child born has access to good nutrition, education, and development opportunities. A paradox exists: while pro-birth policies are in place, higher birth rates are often found in impoverished households or remote areas where parents lack the means to properly raise or educate their children—thus compromising population quality. These disadvantaged children may be more vulnerable to social issues.

Dr Mai Xuan Phuong argues that in order to simultaneously promote fertility and enhance population quality, stronger and more comprehensive policies are required. For large families, housing and public childcare facilities should be made available—ideally within or near industrial zones to facilitate parenting. Children must be guaranteed healthcare through specific health and social insurance policies. Parents should be given employment opportunities to support their children. Viet Nam must improve its education and childcare system—extending tuition waivers beyond secondary school to include preschool. Physical education, nutrition, and school milk programmes must be expanded to enhance children's health and stature. For the elderly, a multi-tiered care network should be developed to meet their increasing needs.

“Public awareness campaigns must shift societal attitudes—fighting stereotypes around childbirth, promoting gender equality, and tailoring pro-birth incentives to specific groups. For instance, we should encourage childbearing among those with good reproductive health, education, and finances—such as young professionals, intellectuals, and entrepreneurs. At times, incentives may be better suited to urban or rural settings. In short, policies must be flexible and adapted to local contexts to mitigate negative population growth and prepare for an ageing society,” Dr Phuong recommended.

The draft Population Law being developed outlines three key policy pillars: maintaining replacement fertility, reducing gender imbalance, and improving population quality. According to Dr Mai Xuan Phuong, these policies are interdependent and must be implemented in tandem. Focusing on one will impact the others.

However, a phased approach is needed: from 2025 to 2030, the target is to prioritise birth encouragement, then manage gender imbalance and lay the groundwork for population quality improvement. From 2030 to 2040, it is essential to stabilise the fertility rate and monitor local variations. From 2040 to 2060, shift focus to gender balance and population quality, once fertility is stable. This approach aims to create a new "golden population"—intelligent, healthy, and highly skilled.

According to the Ministry of Health, Viet Nam sees over 1 million infertile couples annually, around 50% of whom are under 30. The World Health Organisation predicts that infertility will be the third most serious disease of the 21st century—after cancer and cardiovascular disease.