However, a paradox emerges: while educational thinking is shifting towards openness, the management system remains largely closed– from a centralised control model and rigid input regulations to an administratively burdensome programme approval process that lacks flexibility and trust in educational institutions. This disconnect between strategic vision and practical implementation hinders progress.

Therefore, for open education to truly materialise, it is essential to reform the governance of education institutions towards greater transparency, flexibility, and empowerment of creative stakeholders, while establishing effective oversight and feedback mechanisms to replace rigid administrative intervention.

A necessary trend of the times

In a world governed by digital knowledge, the knowledge economy, and the imperative of lifelong learning, the traditional model of education—confined within four classroom walls and fixed in time, space, and content—is increasingly inadequate.

Instead, “open education” is emerging as an inevitable trend, a transformative model that makes knowledge more universal, flexible, and accessible to all citizens, in a learning society.

In its modern sense, open education is not only about broadening the demographic of learners but also represents an educational philosophy, one that puts the learner at the centre, empowering them to choose what, how, and at what pace they learn, based on individual needs.

Open education is inherently linked to the concept of “lifelong learning”—where education does not end at graduation but continues throughout life as a constant necessity in a rapidly changing society.

In Viet Nam’s Education Development Strategy for the 2021–2030 period, with a vision to 2045, the government clearly outlines its goal: “Develop an open education system with lifelong learning, ensuring equity and quality, and gradually shifting to a flexible, modern, digitalised, and internationally integrated education model.”

The 13th National Party Congress’s documents also emphasise: “Build a learning society, develop an open and practical education system that promotes lifelong learning, equity, and efficiency.”

These statements demonstrate that open education is no longer an idealistic option but has become a strategic national direction.

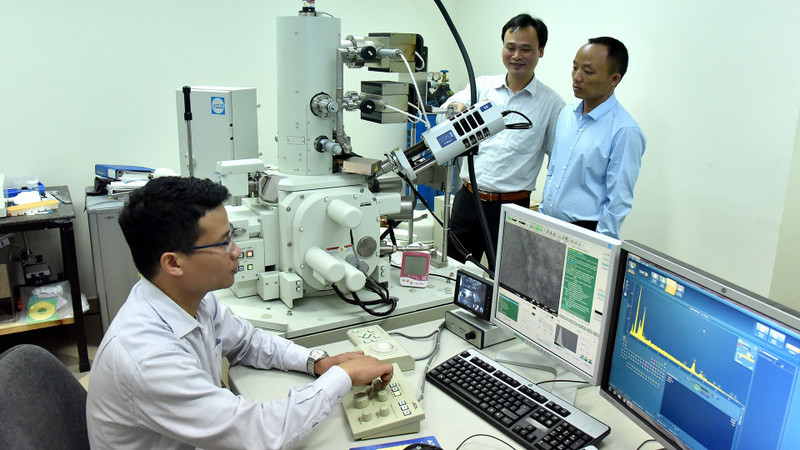

Reality affirms this shift: the COVID-19 pandemic catalysed the transition to open education in Viet Nam. Universities such as Ho Chi Minh City National University, Ha Noi University of Science and Technology, and FPT University developed or upgraded learning management systems (LMS), and launched hundreds of internal Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) to broaden knowledge access — not only for their own students, but also through cross-institutional and interdisciplinary collaborations.

During this period, the Ministry of Education and Training also piloted the recognition of online course credits, laying the foundation for more flexible education in the post-COVID period.

The core issue, therefore, lies not in technology or technical solutions, but in the need to shift mindsets and institutions — from control to empowerment, from fixed approaches to flexibility and personalisation.

This is the key for Viet Nam’s education system to not just “respond” to challenges, but to genuinely “transform” in the new context.

Barriers to education reform

Despite clear objectives for building an open education system in strategic national documents and policies, the implementation of this model faces major barriers rooted primarily in outdated mindsets and institutional frameworks that continue to dominate education governance.

These mindsets are evident not only at the policy level but also deeply embedded in the operations of educational institutions nationwide.

For example, education management in Viet Nam remains overly administrative and command-based, with detailed interventions from authorities in many aspects of school operations.

Rather than acting as “enablers” who build legal frameworks and a conducive environment for institutional autonomy, education authorities still function as “commanders” — issuing orders, imposing procedures, and supervising through administrative paperwork. This hampers the autonomy and innovation of universities, especially public ones.

Although the amended 2018 Higher Education Law expanded autonomy rights for educational institutions, in practice, these rights are still constrained by tight controls over finance, staffing, and academic matters.

Many universities report that they still need approval for each admission plan, to launch new programmes, or that they are bound by strict regulations on faculty titles, standard teaching hours, and tuition caps. These limitations make it difficult to design flexible curricula, a core element of open education, especially amid rapidly evolving labour market demands.

Programme accreditation, recognition of qualifications and credit transfers also remain rigid and inflexible. There is still no clear legal framework for recognising credits from international online platforms or for non-traditional qualifications, like micro-credentials.

As a result, many flexible learning initiatives are either rejected or lack official recognition, creating barriers for learners in pursuing academic advancement or seeking employment.

Consequently, despite its “open” rhetoric, Viet Nam’s education system continues to operate in a “closed” manner. Curricula remain slow to adapt, students have insufficient access to contemporary learning models, and employers frequently note that graduates struggle to adapt to real-world demands.

This has resulted in Viet Nam lagging behind global trends in personalised learning, digital skill development, and lifelong education.

Institutional reform: A prerequisite

The current governance model of education — characterised by administrative rigidity, inflexibility, and superficial autonomy — is the greatest barrier to building an open education system.

Addressing these bottlenecks requires more than technical tweaks; it demands a fundamental institutional shift, from control to support, uniformity to diversity, confinement to openness. This is a prerequisite for Viet Nam to fully embrace the era of open education and a learning society.

Especially amid digital transformation, globalisation, and constant labour market shifts, reforming educational governance towards “openness” is no longer optional; it is essential for Viet Nam’s education system to innovate, adapt, and develop sustainably.

The first priority should be establishing a flexible legal framework that supports open education models. Issuing specialised legal documents — or amending the Education Law and Higher Education Law to recognise non-traditional learning models, standardise Open Educational Resources (OER), and create flexible assessment standards — is imperative.

Institutional reform must go hand in hand with modernising governance to promote transparency and full digitalisation. This requires authorities at all levels to shift from a “command-and-control” model to one of “support and enabling,” driven by data.

An open education system requires transfer of academic power to learners and institutions. For learners, this means choosing subjects based on individual needs, earning flexible credits from multiple sources (including informal and non-formal learning), and having lifelong learning achievements recognised. For institutions, especially universities and vocational schools, it means genuine autonomy in curriculum development, international partnerships, and academic collaborations, without needing approval for every minor detail, as long as they meet standardised quality frameworks.

If the State–school–learner relationship is not restructured towards decentralisation and partnership, open education will remain confined by administrative rules and persistent unequal access to learning.

Moreover, open education cannot operate effectively if financial policies continue to follow the “equal distribution” principle.

New financial mechanisms are needed to support learners flexibly, according to individual needs and capabilities — through models such as open scholarships, credit-based tuition subsidies, flexible education loans, or even “income-contingent repayment” schemes.

Public–private partnerships (PPP) should also be encouraged in developing open education platforms, investing in digital resources, and facilitating school–enterprise collaboration in practical training.

As the world enters an era of open knowledge, open technology, and open learning, education systems that fail to open — both in mindset and governance — will fall behind, squandering human potential and hindering national development.

It is time to shift decisively — from control to empowerment, from rigid regulations to adaptive flexibility, and from administrative command to supportive innovation.

Education cannot be opened by technology or slogans alone; it must be unlocked through genuine reforms in policymaking, institutional operations, resource allocation, and accountability mechanisms.

The call to action is clear: institutional reform is not solely the responsibility of the education sector; it is a cross-sectoral, cross-institutional task directly tied to national competitiveness in the digital age.

Building an open education system requires broad consensus and commitment across society — from lawmakers, government agencies, universities, and businesses to learners — all must transform to adapt. Open mindsets and open policies — these are the only paths to unlocking the future.