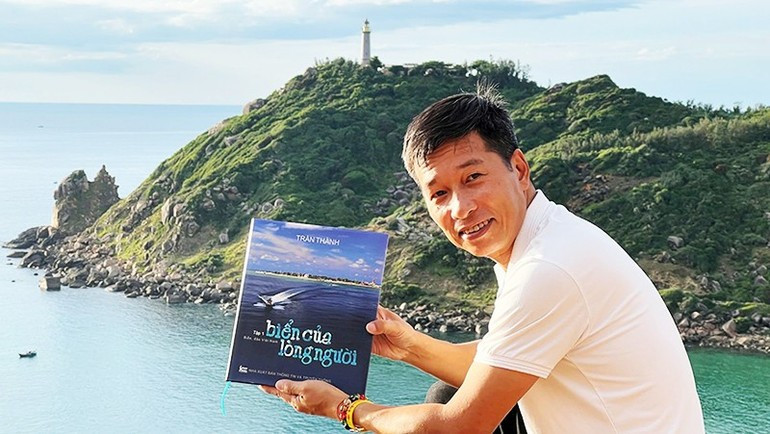

His photo book titled ‘Bien Cua Long Nguoi’ (The Sea of the Human Heart), which was recently released by the Information and Communications Publishing House, introduces readers to these emotional journeys.

Q: ‘The Sea of the Human Heart’ is a unique fusion of photography, poetry, and technology. But more than just technique, it features a heart deeply touched by the homeland’s islands and seas. What truly moved you to dedicate so much passion to this long journey?

Engineer-photographer Tran Thanh: Viet Nam’s islands and seas are sacred territory, where the source of life flows endlessly; where every wave, and every soldier’s and civilian’s face carries a spirit of responsibility, love, and beauty. It is the bond among comrades, teammates, and compatriots who are working in the seas and island regions that compelled me to take this journey seriously.

I am not a professional artist; I am an engineer. Yet, I always believe in the power of sincerity.

For more than ten years, I have used photography to recorded every moment, eventually selecting over 500 photos from among them for this book.

Viet Nam’s islands and seas are sacred territory, where the source of life flows endlessly; where every wave, and every soldier’s and civilian’s face carries a spirit of responsibility, love, and beauty

I also wished to expand this emotional space, so I combined modern technology by using QR codes to allow readers to see and hear the sound of waves, footsteps of young soldiers, and the confessions of mothers of naval soldiers who sacrificed their lives on Gac Ma (Johnson South) Reef to defend the nation's sovereignty over seas and islands.

I want to make memories no longer lie dormant on the page but become vivid, resonant, and far-reaching. This is a precious part of my memories that I give back to everyone.

Q: Have there ever been moments when you were too overwhelmed with emotions to press the shutter?

A: Certainly. Not just once. There were heart-wrenching moments! I vividly keep in mind the farewell of soldiers on the island. A young soldier was about to return to shore after his tour of duty, while the commander stayed behind. The two rested their heads on each other’s shoulders in a very tight embrace. The young soldier quietly wiped away tears and silently turned away, so the commander would not see him cry. I stood there, camera in hand, unable to take a shot.

Another time, a young soldier asked permission to bring back a dog he had cared for the entire year. When approved, he hugged the little dog and dashed towards the pier, rejoicing like a child reunited with a loved one. I stood behind, smiling and tearing up because the bond between humans and this living creature on a distant island was so pure and precious!

Perhaps the most moving moment was the memorial ceremony for heroes and martyrs who sacrificed their lives for the islands and seas.

From the boat, I looked up at the ship where delegates stood silently, releasing yellow daisies and white cranes into the sea. The waves lapped gently, the white cranes floated on eternally. The chill of the water seemed to pierce straight into my heart. I thought of mothers in distant hometowns still waiting for their sons’ return. At times like that, I fully understand sacrifice and gratitude.

Q: As an engineer who has chosen to deeply engage with photography — a field rich in emotion and artistry — have you reflected on any profound connection between the two fields?

A: Many think that technique belongs to reason, while art belongs to the soul — two seemingly separate paths. Yet for me, they are not divided. On the contrary, the more I delve into both, the more I realise that reason and emotion, science and art, both stem from a single origin: the ‘seeing’ and ‘knowing’ of humanity towards the world around us. Reason grants us accuracy; the soul gives us depth.

A technician working only with hands and machines cannot create delicate things, while an artist lacking reason to listen and organise will struggle to reach the sublime. What matters is not what profession you pursue, but how you observe life.

To me, reason and soul are not opposites but two arms working together, helping me reach the essence of a moment, a picture, or a story in this vast sea of life.

Q: Do you think technology is an effective way to bring art closer to the public in the digital age?

A: I think applying digital technology to photo books is an inevitable step in the 4.0 era. Young people today live in a digital world, so I want art — especially the sincere, touching stories from the islands and seas — to enter that world in a more accessible, convenient, and widespread form.

However, I have always believed that technology is just a means; the goal remains the emotional resonance of people before beauty.

Ultimately, art is a precious pause amid the rush of life. Technology offers speed; art provides depth. I want to combine both so the public can come closer to art, and art can open more of its doors.

A photograph that ‘speaks’ is one that stops the viewer, silences them, and makes them feel small before something grand. That feeling still needs to be experienced through real eyes and a real heart.

I enjoy large prints hung on walls, where daylight from the window falls across the image, allowing anyone passing by to pause and wonder: “How did this moment happen? Where is the person in the photo now?”

Ultimately, art is a precious pause amid the rush of life. Technology offers speed; art provides depth. I want to combine both so the public can come closer to art, and art can open more of its doors.

Q: What has caused you the most concern and what gives you the greatest comfort and renewed faith during your creative process?

A: The thing I regret most is my own limitation, specifically my health. During the fiercest sea journeys, with huge waves tossing the boat as if ready to throw everything overboard, I, like many others, suffered severely from seasickness. Sometimes the camera lay right beside me, but I could not pick it up, could not stand steadily, let alone capture precious moments.

I still remember those nights when everyone curled up in their beds, enduring silently, while on the cabin those navy sailors kept the helm steady. They too were seasick and pale-faced, but their hands held firmly to keep the ship on course.

In the galley, the logistics team prepared meals, even knowing no one might be able to eat. Those were the quiet touches of resilience that, regrettably, I could only preserve in my heart, not through the lens.

Yet those very moments became my greatest comfort. The comradeship and brotherhood on this sacred sea are profound. The island guardians readily give their blankets to new guests, offer delicacies to seasick comrades, and quietly share the last sips of fresh water.

From this, I always feel protected, cared for, and uplifted. Every time I visit the frontlines of sea and wind, I am moved by this way of living, with kindness, solidarity, and mutual dedication. That is the ‘human heart’ I want to preserve in this book.

Q: Following the launch of ‘The Sea of the Human Heart’, do you have any upcoming projects to continue inspiring love for the Fatherland?

A: I still have so much left unsaid. For me, the Fatherland always inspires endless journeys. Currently, I am working on two major photo book projects.

The first one is ‘A Circle of Viet Nam’, which will take readers to the nation’s most sacred places: border milestones, extremities — the places where the Fatherland’s borders begin and end, where soldiers and people have developed close attachment to the land, sky, and sea with responsibility and profound faith. I want to tell the story of patriotism through the silent steps across passes and streams, through smiles atop Lung Cu peak, in A Pa Chai, or at Ca Mau Cape.

The second project is entitled ‘Steadfast on the Continental Shelf’. It is a book about the DK1 platform in the southern continental shelf. Amidst the vast sea, Vietnamese soldiers steadfastly holding the waves, the winds, and loyalty.

Additionally, I want to produce more accessible items such as postcard sets and small bilingual photo books with QR codes to spread love for the sea, islands, and borders among young Vietnamese people and international friends.

Thank you so much for sharing!