1

It is not easy to imagine what Mo Rai was like several decades ago, then part of Kon Tum and now belonging to Quang Ngai. Following the memories of village elder A Ren in Le Village, hardship, poverty, and backwardness flicker like firelight. During the years of war, to avoid bombs and enemy pursuit, Central Highlands communities, including the Ro Mam, fled ever deeper into the forests.

Looms lay idle, songs went unsung. Close-kin marriage customs caused the population to weaken steadily; solitary figures drifted in and out of the deep forest, as if on the verge of disappearing altogether. When the war ended, hunger and poverty spilled over into peacetime. The Ro Mam seemed to forget the way home. Seeds once grown for weaving fibres, left unplanted for too long, had perished; the population had dwindled at an alarming rate. With barely over a hundred lives and an uncertain future, it felt like a tragic end was looming for the entire ethnic group.

At that critical moment, helping hands reached out. Policies were turned into concrete action as authorities at all levels from central to local stepped in. The army encouraged the community to gather once more in what is now Le Village, to build houses and cultivate fields. Rubber trees were introduced and planted on the red basalt soil. Soldiers mobilised households to grow rubber on their own land, and for families short of labour, the army helped plant on their behalf.

Once food and clothing were more or less secured, the soldiers patiently explained why the Ro Mam population had been dwindling: marriages between siblings, uncles and nieces — marriages within close bloodlines — had resulted in children who were physically weak and intellectually underdeveloped. Step by step, change came; step by step, recovery followed. Slowly but steadily, in the right direction. The Rong house was rebuilt. Weaving resumed. Traditional garments were sewn again. A community was gradually reborn. Children returned to school.

For many years, the 78th Economic-Defence Unit (under the 15th Corps) has carried out its mission of reviving the Ro Mam community with notable effectiveness. Those who did not wish to farm their own fields could work for the unit. If village life was inconvenient, they could live in the unit’s residential quarters. Life took root and revived, little by little. From a population of just over 100, the Ro Mam in Mo Rai have grown to 187 households with nearly 566 people. Many have become workers at the 78th Economic-Defence Unit, with stable jobs and housing support.

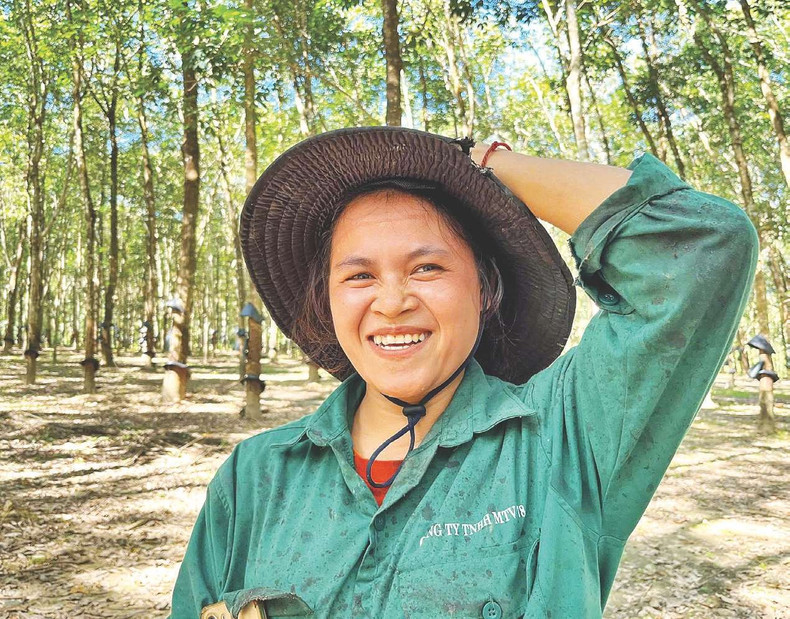

Y De is one of them. I met her at a rubber plantation run by Production Team 11. She deftly tapped latex while chatting, breaking into a charming smile whenever I raised my camera. Following Y De, I visited the workers’ residential area. After work, Ro Mam women gathered in front of their quarters to rest and chat, precious moments before preparing lunch for their families. The command house of Team 11 is also located within the compound. Captain Dau Quang Hung, Head of Production Team 11, noted that the proportion of Ro Mam workers in his team is relatively high compared to others in the unit — with 3 out of 77 workers — partly because Team 11 operates close to Le Village, making it convenient for them to live in the residential area while remaining connected to their village.

2

Colonel Nguyen Van Muoi, Party Secretary of the 78th Economic-Defence Unit, invited us to attend a community gathering held on a Sunday morning. By tradition, once a month the unit slaughters a pig to organise a great unity festival. Residents gather to eat and drink together; those with birthdays that month receive congratulatory gifts, while newly twinned households or families experiencing weddings or bereavements are offered encouragement and support.

There I met the Ro Mam couple Y Hoan and A Doi. Y Hoan was born in 1987, and A Doi in 1992. They are among the new residents of Le Village, having married in 2009 and begun work as labourers with Production Team 10 in 2011. Fourteen years have passed in the blink of an eye. Their first son was just five months old when his parents began working at Team 11; he is now nearly 15 and is attending high school. The couple have since had two more sons, all of whom are growing up well. With an average monthly income of around 15 million VND, their life is relatively stable. Recently, with support of 80 million VND from the Trade Union of the 78th Economic-Defence Unit under the “Great Unity House” programme, combined with their own savings, they were able to build a solid and comfortable home.

3

The story of Y Duc, who was nearly buried alive with his deceased mother according to old Ro Mam customs but rescued in time by border guards, has long been cited as a stark example of outdated practices once associated with Mo Rai.

Later, other children like Y Duc were also saved as the community began to listen and change. A Luong, a local militia member sitting with me, is one such case. His mother died while he was still breastfeeding, but he was spared. Today, he stands over 1.7 metres tall, wearing the uniform of the local militia.

A Luong is a living witness to the changes among the Ro Mam in Mo Rai. Together with Village Head A Thai, Elder A Ren, and Y Vac, he received us in the traditional Rong house, the spiritual heart of the Ro Mam community. A Thai holds a law degree and serves as both Village Head and Party Cell Secretary; he has also been a member of the People’s Council of former Kon Tum and current Quang Ngai. Y Vac, meanwhile, is a young woman who graduated from a college of agriculture and forestry and currently works as a defence employee with the 78th Unit. A Thai said, despite many upheavals, the village has fortunately preserved several dozen sets of gongs in its Rong house.

Later, once the village was re-established and life stabilised, Y Diet, an elderly artisan of the Ro Mam community, made efforts to recall the traditional motifs once used on Ro Mam garments. Drawing on memory and inherited techniques, she painstakingly embroidered them anew. Gradually, traditional Ro Mam attire was rediscovered and folk songs were collected once more.

The government has supported the restoration of traditional costumes so that Ro Mam youths can don the attire of their people during festivals. Certain customs have also been preserved, with ceremonies such as the new rice festival and the ritual to open the granary revived based on elders’ recollections.

We asked to visit artisan Y Diet, A Luong’s grandmother, at her home. She brought out looms and woven cloth made from flax fibres, showing us characteristic patterns of Ro Mam dress. Taking out a half-finished garment, she resumed her work, embroidering as she explained. As she worked, her lips moved softly with songs, those the Ro Mam had not sung for a long time, now returning.

I realised then that a different Mo Rai has taken shape on this land.