From the French colonial period to the day of the Declaration of Independence (September 2), football became a bridge for important political missions, even a tool serving the revolution.

“From the pastime of colonists to a movement of the Vietnamese people”

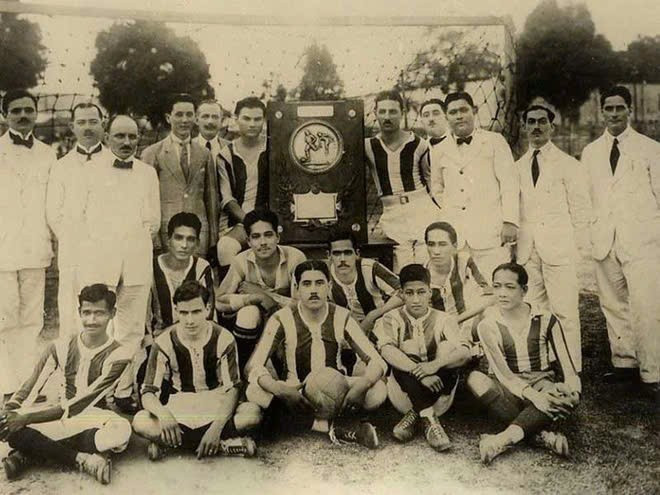

Football followed the French, arriving in southern Viet Nam in 1896, then still called Cochinchina, under direct French rule. Initially, it was a pastime of French soldiers and officials, but it quickly spread to clerks, workers and gradually became popular among Vietnamese.

At Sai Gon Port in 1905, the British Warship King Alfred docked and played a friendly match with a team including French and Vietnamese players. This match is regarded as the first international football match in Viet Nam.

A great turning point came in 1906 when E. Breton, a member of the French Sports Union (L'Union des Sociétés Françaises des Sports Athlétiques) popularised football rules in the southern Viet Nam. Besides promoting the rules, he reorganised Cercle Sportif Saigonnais, a club with a rich tradition at that time in the style of French football clubs.

In a few years, football spread to the central and northern regions of Viet Nam, forming strong teams such as Le Duong Dap Cau, Olympique Hai Phong, Ha Noi Club (Stade Hanoien), and Le Duong Viet Tri.

In the north, football was initially only a pastime played in empty fields and at crossroads. During the 1910s–1920s, Vietnamese teams including Chop Nhoang (Éclair) and Ha Noi Club (Stade Hanoien) together established the Nha Dau Stadium near Long Bien Bridge. Meanwhile, Cot Co Stadium was then called Manzin Stadium, managed by the colonial army.

From being a sport of the French, a pastime of colonists, football later spread widely, and had a profound influence among the people. The French did not imagine that this sport would gradually become a flame awakening the national spirit, and beyond that, the ball itself carried within it the revolutionary spirit.

During the 1920s–1930s, the workers’ football movement spread. Many football teams associated with factories such as Cong Nhan Hai Phong, General Department of Railways, Ha Noi Electricity Workers, Nam Dinh Textile Workers were established.

The purpose of establishing the teams was for fitness and recreation, and to play friendlies against French teams or other Vietnamese teams, as well as to meet and exchange and, in many cases, to organise secret activities. Many revolutionary cadres working secretly were also members of workers’ football teams. Thus, football became a means of uniting the masses, adding strength to the struggling movement for national liberation.

Political mission in the early days of independence

At Ba Dinh Square on September 2, 1945, President Ho Chi Minh read the Declaration of Independence, founding the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam. The joy was incomplete as the fledgling government faced various challenges: “hunger, illiteracy, foreign invaders, and internal traitors”.

After the Preliminary Agreement of September 14, 1946, relations with France became extremely tense. At that time, the French colonialists did not give up their ambition to reoccupy, while we were determined to safeguard independence, persevering with conciliation to gain more time to prepare for resistance. In that context, football was unexpectedly used as a soft diplomatic channel to ease the tense situation.

At that time, Uncle Ho suddenly announced to the people of Hai Phong City that we would organise a football match with the sailors on the French warship Dumont D’Urville, to show the goodwill of the Vietnamese people.

The task of establishing a team was entrusted to star player Nguyen Lan, who had less than 24 hours to prepare. Although time was short, once the organisation assigned a revolutionary mission, no matter how difficult, it had to be done.

That night, Lan rode his bicycle through the streets, searching for each player. After hours of hard work, a “patched-up” football team was formed. Besides names like Luong “short”, Nguyen Thong, Sau “moss”, the team was supplemented with class B players such as Luong, Phu (police), De, Thoat, Giao. Although there was no time for training, everyone was extraordinarily eager and enthusiastic. At the same time, the organisers stressed the friendly playing spirit—no rough tactics, no over-competitiveness—and urged vigilance against reactionaries seeking to sabotage.

Pho Ga Stadium was crowded on the afternoon of October 21, 1946. The red flag with yellow star and the slogan “Support the revolution” flew proudly. The French team consisted of tall players, smartly dressed in uniform. The Hai Phong team, though smaller in stature, was skilful, wearing the traditional yellow uniform of the “Phoenix of the Port”.

In the first half, Hai Phong led 1-0, overwhelming their opponents. In the middle of the match, the organisers directed the team to "give way" for France to equalise, to avoid tension. The second half ended 1-1. The organisers’ biggest concern was that reactionary forces might exploit the match to stir up trouble, provoke, even carry out terrorist acts such as throwing grenades or assassinating players of the two teams to sow division and discord between us and France. Fortunately, this did not happen. That was a major success for the Hai Phong Police force at that time.

The ball – a friendship bridge and a symbol of peace

Through the football match between Hai Phong and the French Navy team, the tense atmosphere between the two nations was partly eased, and the friendship was fostered.

This match not only satisfied the passion of fans in Hai Phong, but more importantly, in the political context of that time—when the independence of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam was still fragile and under many pressures—the match became a soft but effective diplomatic bridge, helping to ease differences, thereby maintaining a channel of dialogue with France and opening opportunities to continue negotiations in peace.

That was truly a “victory” in diplomacy, helping us to protect the independence declared on September 2.

From a game once imported by colonists, football has gradually moved beyond mere entertainment to become an inseparable part of Viet Nam’s political and social life, thereby stirring up national solidarity, nurturing the will to fight for independence and becoming an effective soft tool in diplomacy.

The image of the soldiers-players in that historic match, both throwing themselves into the match on the pitch and silently protecting peace, has been etched into the history of the nation’s sport and diplomacy.

It was not only a beautiful memory but also a vivid testimony that sport, when placed in historical context, can stand shoulder to shoulder with politics in the cause of defending the Fatherland, contributing to protecting independence, sovereignty and spreading the message of peace to international friends.