In 1969, while studying a Party resolution, participants received the sorrowful news that President Ho Chi Minh had passed away. Deeply moved, artist Vo Dong Minh made a solemn vow before the late President’s spirit: if he survived the war, he would paint 79 portraits of Uncle Ho, representing the President’s age, because the people of southern Viet Nam had never seen him and always longed to meet him.

According to Vo Dong Minh’s recollection, at that time, the Head of the Tay Ninh Provincial Party Committee Commission of Popularisation instructed the building of a temple to worship Uncle Ho. Immediately, students began digging the earth and moulding bricks to build the temple in a forest. The Commission of Popularisation assigned artists Vo Dong Minh and Tam Bach to paint a portrait of President Ho Chi Minh to place on the altar for the memorial ceremony. In tears, and before the President’s spirit, Vo Dong Minh vowed that if he survived the war, he would paint 79 portraits of Uncle Ho, because the people of the South had never seen him and always longed for the opportunity. Conversely, President Ho also yearned to visit the southern compatriots when he was alive. For that reason, the artist was determined to paint 79 portraits of Uncle Ho to help the people of Tay Ninh, and those in southern Viet Nam, understand more clearly about him.

At that time, printing technology was still primitive and the published portraits of Uncle Ho in newspapers were unclear. The artist wanted to use fine art to depict a clearer image for the southern people to see after liberation. And so, even in the years following national reunification and scientific and technological advances, with many new images of Uncle Ho available, he remained committed to his promise. He painted tirelessly while working in cultural information, preservation, museum management, and Party activities. Each year, around President Ho’s birthday, he would set aside time to paint one portrait. In the difficult early years after liberation, with no means to purchase art materials, he chose to use a metal nib pen to draw portraits of President Ho.

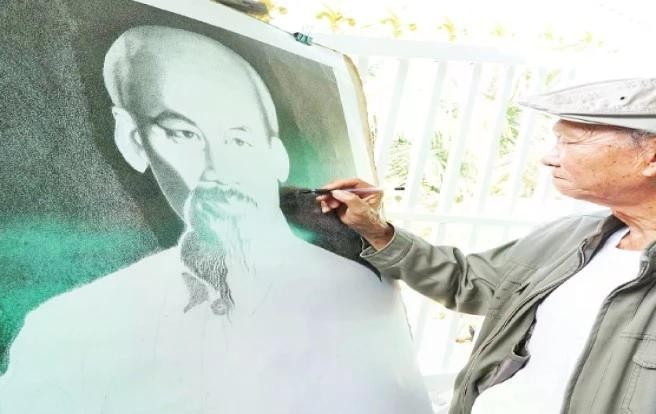

Artist Vo Dong Minh recalled that he initially drew Uncle Ho’s portraits on small grid paper. As he neared completion of the 79 portraits, he realised that such small formats could not capture the dignity and grandeur of Uncle Ho. He then switched to drawing on large-format Roki paper, about 80cm x 110cm. Each stroke with the metal pen was slightly thicker than a strand of hair. As a result, it took him about two months of continuous work to complete one large-format portrait, with each piece averaging three months of labour.

To create the portraits, the artist had to expend great effort travelling far and wide to collect reference images from various historical photos and angles. He often worried whether he would have enough time and strength to complete his dream. Fearing that old age might prevent him from fulfilling his vow, he sometimes woke as early as two or three in the morning to sit at his easel. After half a century of diligent and respectful work, in 2023, Vo Dong Minh completed the greatest undertaking of his life. Today, his 79 beloved portraits of Uncle Ho are either framed under glass or stored in plastic covers for careful preservation. However, this labour of love has not reached the people of Tay Ninh and southern Viet Nam as he had hoped.

According to the artist, in earlier years, when he had finished just a few dozen paintings, Tan Bien District (Tay Ninh) exhibited the collection a few times. Last year, someone tried to negotiate an exhibition of all 79 portraits in Nghe An Province – Uncle Ho’s homeland, but he declined. The exhibition was to be held outdoors in a garden, and he feared that sunlight might damage the works. Another individual from Ho Chi Minh City also visited several times to ask to purchase the entire collection, but the artist refused to sell. He wanted to preserve the portraits for the people of Tay Ninh and the southern region, in keeping with his lifelong commitment.

Vo Dong Minh, real name Nguyen Van Lam, is now 85 years old and originally from Long An Province. In 1950, as a young boy, he followed his parents to settle in Tay Ninh. Ten years later, he began studying painting under a local artist in Toa Thanh District (now Hoa Thanh Town, Tay Ninh Province). He later enrolled at the Sai Gon College of Fine Arts but left after one year to answer the call of the nation and joined the revolutionary movement.

With his pen as a weapon, he followed revolutionary soldiers across battlefields, painting numerous works on the resistance.

His works vividly captured the fierce spirit of resistance of our army and people.

After peace was restored, artist Vo Dong Minh continued producing art that critiqued social ills. His drawings, under the pen names Vo Dong Minh and Nguyen Dong Minh, were published in newspapers such as Quan Doi Nhan Dan, Thanh Nien, Tuoi Tre Cuoi, and Tay Ninh. He received awards at the 1996 National Propaganda Poster and Cartoon Contest and the Xuan Hong Literature and Arts Award of Tay Ninh Province in 2013.