The core of cultural industries

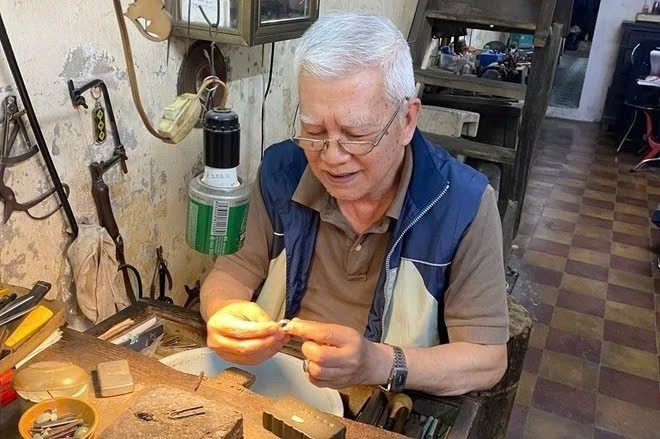

Amid the bustle of Hang Bac Street there remains a small shop owned by Nguyen Chi Thanh. The shop opened more than a hundred years ago, and Thanh is the fifth generation to carry on the goldsmith’s trade, working diligently each day at an old wooden bench.

The tinkling sound of a small hammer is a reminder that Ha Noi still preserves a fragment of its old memory, through the slightly trembling yet steady hands of an elderly goldsmith.

“People come to photograph my shop a lot. My family has been in this trade for five generations; it’s enough to make a living, not to get rich,” Thanh smiled gently.

Thanh’s story is vivid proof that the value of traditional craft villages lies not only in their products, but also in the people themselves and the stories they carry.

Nowadays, visitors to the craft streets come not merely to buy an item; they come to “buy” stories and cultural experiences. These very stories imbue handicrafts with a soul and turn ordinary artisans into captivating “storytellers”.

In the context of globalisation, the concept of “cultural industries” is no longer a distant theory; it is becoming a new, highly promising path to revive and develop craft villages.

Cultural industries are not simply about making products; they are the process of exploiting, creating, and commercialising cultural values, transforming traditional heritage into attractive and highly competitive products and services.

Artisans and craft villages are the nucleus, the heart of this transformation. They are not only the makers of products, but also the “storytellers”, the “creators” who possess invaluable knowledge and skills. Each handicraft item contains a story of culture, history, and people.

To harness this potential, the state and Ha Noi authorities have implemented comprehensive support policies.

The government and Ha Noi have put in place policies to honour and confer prestigious titles such as “People’s Artisan” and “Meritorious Artisan” under Decree 62/2014/ND-CP. These titles are not only a form of recognition but also come with appropriate benefits such as financial support and health insurance. This helps artisans feel secure in their livelihoods and dedicated to their craft, keeping the flame of cultural storytelling alive.

An outstanding example is artisan Tran Do, known as the “wizard of ceramic glazes” in Bat Trang. As the village’s sole People’s Artisan, he has painstakingly restored many ancient glaze lines, including celadon and blue-and-white glazes, contributing to the preservation of Viet Nam’s ceramic heritage.

The story of Ha Thi Vinh is another testament to the intersection between tradition and modern business thinking.

As one of Bat Trang’s few leading female artisans, she has not only mastered traditional techniques but has also boldly renewed production thinking. She revived a family business and modernised production processes while preserving the handmade spirit and the finesse of each product.

Vinh has shown that for traditional crafts to survive in the new era, skill alone is not enough; the acumen of an entrepreneur is also essential.

The combination of the traditional craftsmanship of Tran Do, the business vision of Ha Thi Vinh, and the creativity of the younger generation such as artisan Vu Nhu Quynh has created a vibrant mosaic of today’s Bat Trang ceramics.

Similarly, in Phung Xa Silk-Weaving Village (My Duc District), the story of artisan Phan Thi Thuan is another example of creativity. She not only preserves the traditional craft but has researched and created unique lotus-silk products, turning what once seemed impossible into reality.

Access to finance: A core development issue

Despite many support policies, access to capital remains a major barrier for many artisans and small production facilities. Preferential loans from funds such as the Rural Development Support Fund under Decree 52/2018/ND-CP are a practical solution. However, many artisans still face difficulties due to complex administrative procedures and a lack of collateral.

To address this, capital support policies need to be reformed towards greater flexibility. Instead of relying solely on traditional collateral, microcredit models suited to the characteristics of handicrafts are needed, potentially based on an artisan’s reputation or guarantees from craft village associations. In addition, direct support from local budgets in the form of seed funding for technology innovation or environmental treatment projects is also an effective measure. This would enable artisans to invest with confidence, improve productivity and product quality, and thereby create higher-value goods.

Building brands and stories

In the era of cultural industries, handicrafts are no longer the sole objective. They are also part of a broader value chain that includes experiences, services, and storytelling.

Enhancing the promotion of the image of artisans — and, more broadly, craft villages — not only helps them to make a living from their trade but also plays an important role in shaping attractive tourist destinations. Instead of being merely places of purchase, craft villages have become cultural spaces where visitors can meet and converse with keepers of the craft flame and witness first-hand the making process. These unique experiences have transformed craft villages from simple production sites into “cultural tourism destinations”.

Ha Noi is proud to possess a rich and diverse treasure of craft villages, an endless source of inspiration for experiential tourism.

In the context of globalisation, the concept of “cultural industries” is no longer a distant theory but is becoming a new, highly promising path to revive and develop craft villages.

Visitors can stop by Van Phuc Silk Village to admire soft, delicate fabrics; go to Chuong Conical-Hat Village to see artisans crafting traditional hats before their eyes. In Phu Vinh Bamboo and Rattan Village, visitors can discover exquisite handicrafts, while Chang Son Fan-Making Village is famous for its meticulous, beautiful paper fans. One cannot fail to mention Ngu Xa Bronze-Casting Village, Quat Dong Embroidery Village, Vong Young Rice Village, or Dao Thuc Water Puppet Village — each bearing its own distinctive cultural imprint.

Artisans and craft villages should be included in “Ha Noi travel notebooks” accompanied by their unique stories.

For example, when visiting Bat Trang Pottery Village, tourists should not only buy ceramics but also take part in hands-on pottery experiences.

Tour itineraries should also be designed so that visitors can call at Thanh’s shop on Hang Bac Street, hear his stories and admire the art of handcrafted silver. This not only provides a sustainable source of income but also helps spread Ha Noi’s traditional cultural values to international friends.

Craft village products should also be widely promoted on digital platforms. Creating stories and short documentaries about artisans and their craft processes will attract public interest.

Visitors should be able to find artisans and craft villages in online “travel notebooks”, accompanied by unique stories. This helps craft villages reach a wider market, especially international tourists.

Cultural industries are not opposed to the products of traditional craft villages and streets of old; rather, they are the pathway for these villages and streets to exist and develop in the 21st century. By combining the core values of handicrafts, the creativity of artisans and the support of the state, traditional craft villages will not only be revived but also open up new, promising directions, contributing to the overall development of the nation’s economy and culture.