When sacredness becomes distorted

In traditional Vietnamese culture, sacredness is not confined to religious or spiritual beliefs. It also stems from faith, memory, and the emotional bonds of the community passed down through generations.

An old banyan tree, a village well, a royal decree, or a wooden statue, though perhaps lacking in material value, are sacred because generations have connected with them, worshipped them, and entrusted their spirits to them.

Many national treasures, such as the Thousand-Hand, Thousand-Eye Avalokiteshvara statue at Me So Temple, the Ngoc Lu bronze drum, or the bell of Van Ban Temple, once existed in ritual spaces and were intimately tied to community ceremonies.

For the ancients, objects held true value only when they possessed a soul. Bronze drums were not merely musical instruments; they were central to ceremonial life. Buddha statues were not simply sculptures; they embodied places of faith.

When artefacts are removed from their cultural and spiritual contexts, even if their physical form remains intact, they are regarded as having lost their soul.

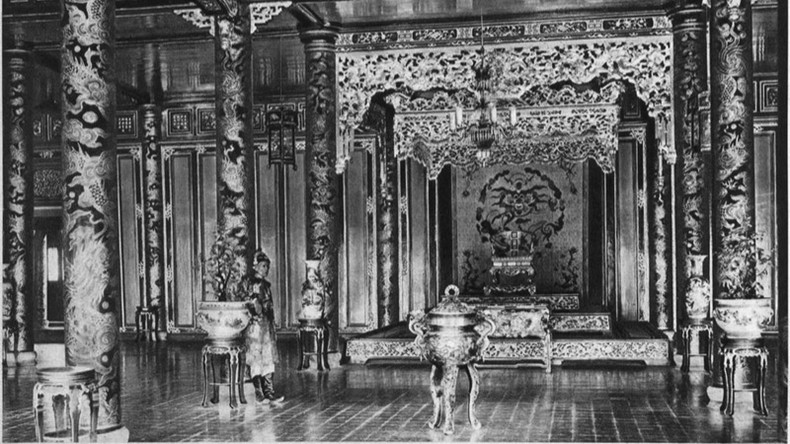

The act of a man climbing onto the imperial throne is not merely offensive, it is a profound insult to the sacred memory of a nation. The imperial throne is more than an antique; it is a symbol of imperial authority, court rituals, social order, and historical continuity.

When sacred symbols are violated, it signals a broader decline in the sacredness of cultural and spiritual spaces, where core values are being gradually eroded.

|

| Imperial throne in Thai Hoa Palace. (Photo: Department of Cultural Heritage) |

This desacralisation affects not only artefacts but also many traditional festivals.

From the procession at Ba Chua Kho Temple in Bac Ninh, the water procession in Nam Dinh, to the harvest prayers of the H’Mong people in Yen Bai—rituals deeply rooted in agriculture and folk beliefs—are now increasingly theatricalised and repurposed for tourism.

Numerous religious structures have also undergone modernised renovations, with ceramic tiles replacing ancient floors, corrugated iron roofing supplanting traditional materials, and old statues substituted with cement replicas painted with emulsion.

Spaces that once demanded reverence and quiet for worship are now losing their spiritual depth. Even museums, designed to foster contemplation, sometimes employ excessive sound and lighting, disrupting the solemnity required. Many visitors fail to maintain appropriate decorum before sacred objects—climbing on artefacts for photos, touching them indiscriminately, or tossing coins onto altars.

Heritage experts have warned that once the sense of the sacred is lost, nothing can truly replace it. However valuable an artefact may be, if stripped of its cultural context and spiritual significance, it becomes nothing more than a lifeless object.

Restoring sacredness to heritage

Though the issue of desacralisation has been raised for years, coordination between the cultural, tourism, and education sectors remains lacking. Preserving sacredness goes beyond protecting the physical appearance of heritage; more critically, it requires safeguarding the spiritual essence revered and transmitted by communities across generations.

This is especially true for intangible cultural heritage, where sacredness resides in rituals, space, timing, and the people who practise them. Take, for example, the Red Dao people’s rite of passage: its sacredness lies not only in the vibrant costumes and ceremonial music, but also in the ritual transmission from master to disciple, bridging the living and the ancestral.

|

| Rite of passage of the Red Dao people in Lao Cai. (Photo: VU LINH) |

Sacredness cannot be artificially reconstructed—it must be preserved through the living traditions of the community.

In museums, restoring sacredness to heritage means carefully recreating original contexts through thoughtful display, lighting, sound design, explanatory texts, and storytelling that awaken reverence in the hearts of visitors.

The Kyushu National Museum in Japan exemplifies this approach. Buddha statues are displayed under soft lighting, in quiet spaces with meditative music, creating an atmosphere of solemnity and reverence for visitors.

Equally important is restoring the central role of the community. Artisans, ritual practitioners, shamans, and spiritual leaders are not merely participants in ceremonies—they are guardians of cultural knowledge and bearers of the spirit of heritage.

When festivals are managed by commercial event companies, sacred rituals can easily be reduced to theatrical performances. Without clear boundaries between sacred and touristic spaces, the risk of distortion becomes increasingly severe.

To counteract the decline in sacredness, a fundamental, interdisciplinary approach is required—from education to legal frameworks. Children must be instilled with a sense of the sacred from an early age—through ancestral beliefs, village ceremonies, and respectful behaviour towards heritage and monuments.

In many culturally rich nations, teaching children about morality, rituals, and reverence for history is considered an essential part of their path to adulthood. Alongside this, it is crucial to improve the legal framework for protecting national treasures, strictly regulate renovation activities, and prevent the commercial exploitation of heritage.

Moreover, support policies for heritage preservation teams are vital to ensure that sacredness is not lost amidst modernisation.

Within the cultural lifeblood of the nation, heritage is not simply a collection of ancient artefacts—it is made sacred by its connections to belief, memory, spirituality, and communal identity. In the face of growing desacralisation, preserving and restoring sacredness in heritage is not only an act of cultural preservation but also a way of rebuilding faith, strengthening identity, and sustaining spiritual foundations for future generations.